Man cannot endure his own littleness unless he can translate it into meaningfulness on the largest possible level

Ernest Becker

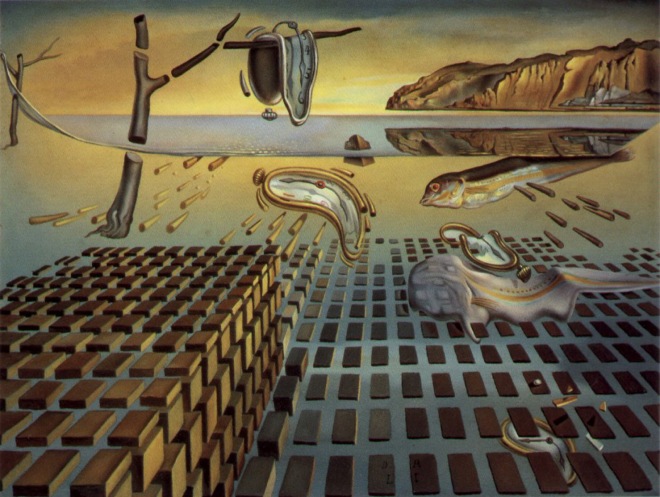

Fear of the passage of time

I recently came across the term chronophobia in the context of people doing exams: knowing that exam day is ever closer makes people anxious. Chronophobia was defined as an experience of unease and anxiety about time, a feeling that events are moving too fast and are thus hard to make sense of, in “Chronophobia: On Time in the Art of the 1960s” by Pamela Lee.

Chronophobia isn’t a formal diagnosis, neither does it feature in scientific literature. In other words, it’s not really a phobia. It is more of an unpleasant feeling – one that is often expressed in art.

It is common in prison inmates, students in long academic programs and the elderly. When one is anxious, it is not only possible to be anxious about the event, but also its inescapable approach. Chronophobia is less about the doom and more about it being impending.

Chronophobia appears to be connected with heightened awareness of the passage of time that is inherent in distant deadlines for significant events.

This morning during my 10 minutes of mindfulness, something interesting bubbled up. I randomly remembered myself on an airplane travelling back to Moscow to visit family about 2 years ago. I felt a strong urge to be that person again, a bit like when I’m on vacation and towards the end, with a sigh, I think back to how liberating the first day off felt. Or when I reach the last bite of some dopamine-explosive dessert, I think back to how happy I felt when it was just put in front of me. We all love vacation and desert. However, my wish to be 2 years younger makes little sense. I was in the throes of a challenging 70-80 hours per week medical rota. It took much ingenuity to carve out enough time to travel. Is it regret? It wouldn’t be fair to say that the last 2 years were somehow a waste of time in any regard. Why do I feel so drawn to the thought of going back in time?

Fear of opportunity cost

Aged 27, I frequently contemplate what it would go back to a previous point in time. I think it’s the understanding of the limited nature of time. I also worry about opportunity cost. In economics, there is the term opportunity (alternative) cost is the value of the option that we don’t choose when making a decision. [If I have 1 euro and buy a 1 euro can of Coke, I would have to forego the 1 euro Mars bar in order to have it. I would thus potentially worry about what it would have been like if they got a Mars bar instead.] The feeling is different to decision-anxiety. It’s not even about second guessing one’s choice, but more about imagining alternative paths.

The word decision literally means the cutting off – of other options. Thinking of the alternatives always reminds us of the unyielding nature of choice and how we really can’t literally “have it all”.

Robert Frost’s famous (infamous?) “The Road Not Taken” is a brilliant and often misinterpreted examination of the nature of choice. It is important to recognise the speaker’s deliberation: he says the roads are much the same: “just as fair”, “really about the same”, “equally lay”.

“The Road Not Taken”, a frequent feature of post-card philosophy, is often oversimplified to say that the speaker chose the less travelled road – and, woohoo, that’s amazing. It’s more complex than that.

The speaker admits that he left the first road “for another day”. While he knew he would never go back, the torment of admitting the final nature of choice is just too much.

One can get very detailed when describing their particular fear. I certainly don’t support the idea of including “fear of opportunity cost”, “fear of the passage of time” or even “fear of choice” as phobias into the DSM. Indeed, this is perfect ground for thinking by induction. Is there a common thread here?

Boiling down fears to a common denominator: could it be death?

Why does chronophobia affect students? Time forces them to deal with events that will affect serious aspects of their lives such as their future careers – and thus even more permanent things like social class, the kind of people they will be likely to marry and so on. Exam results’ effects are by no means definitive, but probabilistically they are significant.

It has become popular to say that there are only 2 human emotions: fear and love.

Everything negative is a form of fear. It kind of makes sense: anger is a way of defending one’s point of view, property or whatever other boundary. Being sad is a fear that one will never be as happy as they were before as a result of an event (not talking about depression here). Disgust is a fear that something will negatively impact one’s existence. You get the gist.

The other popular thought is that all fear is a form of the ultimate fear – of death.

Going back to chronophobia again, why does it affect the elderly? Time threatens the existence of the elderly. It threatens all of our’s existence, but the elderly are more aware of it – mostly for social and cultural reasons. Now, none of us are deluded enough to actually think we’re not going to die. However, as Ernest Becker points out:

we have 2 ideas of the self: the physical and the symbolic.

In my opinion, our rationality only extends as far as the physical self. We are preoccupied with ways to immortalise our symbolic self. As per the “Mahabharata”:

“The most wondrous thing in the world is that although every day innumerable creatures go to the abode of death, still man thinks that he is immortal”.

The recent debate that followed my discussion of the role of validation in our self-esteem sparked some follow on thoughts. In short, it showed that people with narcissistic tendencies experience much emptiness or even self-hatred – and validation is used to take the edge off. However, as all creatures who make choices, people with narcissistic tendencies are subject to avoiding pain and seeking pleasure (thank you, Dr. Freud). Clearly, they find narcissism more tolerable that the alternative. How could this be?

What if those who crave validation to feel good about themselves chose to be this way because the alternative – knowing that one is inherently valuable, without any validation – makes the thought of inevitable death absolutely intolerable? If one feels that they’re not that valuable, dying isn’t quite as scary or tragic.

Realising that a person is valuable, getting attached and then letting go is much harder than never getting attached – in this case to your self, as is the case with death. This devaluation allows people to cope with the fear of death. At the same time, the person with narcissistic tendencies maintains the upside of being able to work on “their immortality projects”, like winning medals and getting promotions. This is just a hypothesis of mine. I understand that I have no idea what Steve Jobs was really like. A lot of people say that he was an obnoxious narcissist. He said this, which happens to be congruent with my hypothesis:

Remembering that you are going to die is the best way I know to avoid the trap of thinking you have something to lose. You are already naked. There is no reason not to follow your heart.

There are other psychologically sneaky ways that we deal with the fear of death that have stood the test of time (well, since 1974 or so when “Denial of Death” was published):

Becker argues that everything we do: writing books, starting businesses, having children are all ways to transcend – and not have to deal with – death.

It makes sense too: the thought that everything one ever does will disappear into oblivion is so hard to accept that in order to keep going we find ways to defy death’s erasure of our existence by leaving a legacy.

One’s own death is hard to imagine. It is as if we believe we will still be alive on some level after we die, but unable to act on our dreams and stuck reminiscing of the time we were alive and lamenting we didn’t do more.

If leaving a legacy isn’t an option, then one can choose to believe in the afterlife to help themselves cope with the concept death.

Paradoxically, dying may be a way to transcend death. Physical death could be a route to symbolic immortality. Just think of war heroes.

While death could explain a lot of our autopilot behaviour, we don’t seem to want to think about it very often. We are told to think positive thoughts instead.

To think, or not to think – about death

Constant reminders of death were common all throughout the last millennium: having a skull on one’s desk was kind of like having sticky notes or an extra mouse. An experiment where people were asked to write about death before they were asked about their country’s war efforts showed that thinking of death made people more enthusiastic about war -as it adds meaning, purpose, a sense of belonging, a feeling of impact…

The Stoics came up with a variety of reasons and hacks to not fear death such as the symmetry argument: fearing death is like fearing the fact that one wasn’t alive before one was born. I won’t go down the rabbit hole of explaining how to fear death less.

The purpose of my reflection isn’t to say we shouldn’t fear death, and it will all be fine. It is more of an inquiry into what behaviours of ours are motivated by the fundamental, underlying fear, which so far appears to be that of death. However,…

It’s not death we fear, it is not having an impact

Is it really death we fear? I think a better way of putting it is that we fear that we’re inconsequential, insignificant, that we made no difference through our existence.

For those who insist that it is a fear of death: it’s that of the symbolic self. For those who insist that our biggest fear is to not be loved: to have someone love one is probably the biggest impact one can have on another human being. Perhaps, it is the ultimate, or the one that really count. I am not sure. However, my point remains: it is about impact.

It could just be a millennial’s take on it. With a lesser role of traditional religion in today’s society, millennials have the unfulfilled need for meaning – and have a habit of finding it in the most peculiar places.

My recent discussion of meaning according to Nietzsche prompted many to comment that the fact that we die and that the universe will ultimately end (something to do with the Sun and physics) implies that there could be no meaning in our lives. I don’t follow this argument. To me, it is like saying there’s no point in eating because you’ll get hungry again. Clearly though,

for a lot of people death is the ultimate enemy in a game rigged against them.

I used the word impact above for a reason. I could have said consequence or meaning, but something stopped me. Both of those words are overused and call to mind all kinds of associations. Furthermore, I thought of animals. They are driven largely by the same evolutionary forces as we are, and I think we overestimate the extent to which animals are different. They may not have insight, but they are a reflection at least of how nature intended things. To illustrate, I will use an example I recall from watching a BBC documentary on giraffes. Two massive male giraffes were fighting for a female. How on earth do giraffes fight, I hear you ask. Well, they violently swing their entire necks to strike. The force of the swing is enough to shatter their skulls. The battle went on to the point of near death… for the sake of a female. The giraffes decided/were driven by nature to go that far just to reproduce – so death is less important than an opportunity to have impact, which, for giraffes I think is reasonable to assume, is to have progeny.

I don’t think that the fear of not having an impact is the same as the fear of failure. One can fail, but still achieve a lot and have an impact. Failure is defined in terms of a percentage of the way to realising a dream. Impact, or lack thereof, is much more real.

I feel that a human being on their death bed is likely to think of what impact they have had, not where they ranked compared to their dream.

On the bright side…

There is a “cure” for fear of choice

Going back to my own ENTP-torment of being more interested in talking about choices rather than actually making them, I am looking for some kind of resolution. N. N. Taleb, a favourite writer of mine, is popularising the concept of optionality. He argues that having options is a great thing:

Optionality is the property of asymmetric upside (preferably unlimited) with correspondingly limited downside (preferably tiny).

It’s not really a way to get out of making choices. Instead, it is a way to do what you were going to do anyway, but leaving cheap enough nets here and there to see if one day something nice washes up in one of them such that covers the cost of having had the nets n times over.

He argues against specialisation (i.e. going down too far in the decision tree of choices or going down to the end of just one branch). We are all familiar with specialisation success stories. The Nobel Prize goes to the person who studied a particular enzyme for 30 years. The startup that solves a specific problem in one particular niche is the one that does well. Kim Kardashian has one thing going for her, and she’s taken over the world…

Taleb reminds us that there are cemeteries of specialised ventures and people. Just because the successes that make into the media are specialised, doesn’t mean all of them are. Specialisation comes from the propensity to make choices. It is not the only way to achieve something. Hence, it is possible that the act of making choices is overvalued.

Richard Branson has over 400 companies. Is it because he is greedy – or perhaps because he understands that specialisation is a dangerous game to play? Venture capitalists and angel investors back things in a non-specialised way. All financial investors do. It may look like it is specialised on the surface, but it really isn’t. Biotech, or robotics, isn’t a specialisation. These are incredibly broad fields. It’s like saying blogging is a specialisation. Investors take directional bets once is a while, i.e. ones that really require a choice, but they do so in a way that for every 1 euro they invest, they stand to gain 10, and only invest a tiny fraction of their euros into these schemes. This is exactly congruent with Taleb’s definition of optionality.

I have fabulously rationalised away the pressure to make choices here. However, the real work is in putting oneself into situations where optionality can be exercised.

The older I get, the more I realise that there’s quite a lot of engineering involved in all of this. It’s not so much about going after specific visions, but creating situations where visions can flourish – and ultimately have an impact.

You may also like:

Millennial corporate office workers and their transgender bathrooms

Nothing like a bit of airy thoughts to lighten the day eh?

I picture myself, one arm hooked over the edge, swirling around a blackhole of metaphysical existentialism, my thoughts and mind slowly being stringified. To lever oneself up, dust oneself off and go fishing, say. That would be a nice day, fishing, I think.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha, well I stayed silent for a whole 2 days while this was brewing! Anony Mole’s gone fishing, everyone!

LikeLiked by 1 person

O to have been brought up on bays, lagoons, creeks,

or along the coast!

O to continue and be employ’d there all my life!

O the briny and damp smell-the shore-the salt weeds

exposed at low water,

The work of fishermen-the work

of the eel-fisher and clam-fisher.

~~~

Yet, O my soul supreme!

Know’st thou the joys of pensive thought?

Joys of the free and lonesome heart-the tender, gloomy heart?

Joy of the solitary walk-the spirit bowed yet proud-the suffering and the struggle?

The agonistic throes, the extasies-joys of the solemn musings, day or night?

Joys of the thought of Death-the great spheres Time and Space?

Prophetic joys of better, loftier love’s ideals-the Divine Wife-the sweet, eternal, perfect Comrade?

Joys all thine own, undying one-joys worthy thee, O Soul.

~~~

http://www.inspirationalstories.com/poems/poem-of-joys-walt-whitman-poems/

LikeLiked by 1 person

You know people always give a look when I say it, but I really love American poetry. Thanks. I feel light and airy already 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s unfortunate, but true that we live our daily lives through a relative paradigm, meaning that we are more often than not comparing our facts / realities to what ideal we have in our head. However, when we die, as you said, we find meaning in the actual impact that we had, an absolute paradigm. As I look back at “states of my life” (jobs, romantic relationships, friendships) that I’ve completed, that have effectively died out from relevance, I can clearly see that many of the struggles I felt were a result of me trying to reconcile reality with a mental ideal, which of course is always a losing battle.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You know that’s a concept I struggle with. I can see the downsides of having no “ideal in my head”, but to not have one doesn’t seem right either. Are we meant to just float downstream or try and have a direction? What do you think?

LikeLike

I think ideals can become problematic if it leads one to rely too heavily on the ideal and as a result, develop some expectation for a resolution in our lives that would actualize our ideals. When you develop this resolution-focused mindset, you attempt to solve for this ideal state that is impossible to reach. I think we need ideals, they provide direction as we search for purpose, but it is dangerous to take them literally. I keep coming back to Aristotle’s principle of moderation as I experiment to figure out how to live my life…I live with ideals but not just with ideals.

LikeLiked by 2 people

You know, you’re probably right. It is all about balance, but sometimes people say that just because it is a non-falsifiable statement, so I always want to dig deeper. I think I am naturally very goal-directed, so it is a journey for me to find that balance. Do you read Aristotle’s original works – or do you have some other way of studying his philosophy?

LikeLike

Thank you, I thoroughly enjoyed reading this. And right at the end you refer to your ENTPness…well I’m INTP apparently and you said everything I want to say 🙌. I also turned 27 last week..only confirmed my existential crisis!!

Your point on opportunity cost – I find this a strange one to get hung up on, generally, I mean isn’t there an infinite amount of alternative outcomes linked to the other decision? How can this cost be calculated?

The poem by Robert Frost is one of my favourites. It relates to the arrow of time, not the insight that the traveller thinks he has!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I get what you mean. I think it’s just trying to learn from the choice – and modelling all the other possibilities, not really calculating the actual opportunity cost. Thanks for connecting INTP – love your blog:)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post.

I have a slightly different hypothesis; I think at the root of chronophobia is a fear of taking things for granted / not making the most of things – ultimately a fear of future regret.

I’ve been thinking about the whole passing of time / ageing thing quite a lot recently, and this fear of future regret feels true for me at least. I don’t (consciously) fear death itself, but I do fear lying on my death bed and realising how much I took for granted and how little I appreciated things at the time.

I’m trying to work on this through mindfulness – at least to try and “check in” occasionally to notice the present moment rather than living on autopilot.

Thanks for posting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting point, a bit like FOMO I guess? It’s a related concept, I think. Making the most of things, to me, is the same as having an impact. Different words work better for different people. Thanks for connecting 🙂

LikeLike

How about being alone? I found that’s a big one for me… And yet the paradox is – no one can really “die with you.” Enjoy what you did here. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You mean we fear being alone the most?

LikeLike

Well – I can’t claim to know about others and it might be different for more antisocial individuals but for me personally it’s a big fear that drives many smaller ones. For instance, I’m afraid of losing finances, or losing relatives, or losing my job, or losing my capacity to work – but underneath those fears is the fear that I will be alone and will not be loved. I’d say it trumps any kind of physical discomfort. As far as death, I guess after thinking about it for some time I’ve made some peace with that.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, the fear of “I am not enough to be loved” is a serious one too. I think it may even be deeper than lacking impact – because what’s the need for impact? Is it to be deserving of love?

I kind of thought about this a lot. I think relying on others to love you is a losing game. It sounds kind of psychopathic like that, but I explain what I mean here: https://thinkingclearly.co/2017/01/07/validation-and-self-esteem/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh yes! I like it when people get real with the personality disorders. So many never make it to those.

But I submit this “losing game” you speak of is unavoidable. Trying to avoid it might be a common trap. Say, at the end of a bad relationship you tell yourself “I will not rely on external circumstances for validation, I will find happiness on my own, I will get tough.. I will… do yoga…” And then you get tough and, to a point, you become wiser and then… some day… you start talking to someone in your Yoga class… and maybe 6 months later you can’t imagine your life without that person. You’re once again dependent on something external!

In other words, our need to be loved – in some capacity – is largely built in and, shall we use a relevant word, inalienable.

Or, in the words of Alan Watts: “there is nothing you can do to transform your nature into unattached selflessness – because you have a selfish desire to do so!”

Every once in a while the Hermits try to prove us wrong when they retreat into a cave, all alone, for years. But then they often come back with powerful teachings they must share with everyone 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha, great point about the hermits. I think you’re right. What I meant was that we have a tendency to attribute a huge weight to other people’s opinion of us (as in personality disorders). It is really hard to not feel that the world centres around you, as our brains seem wired to see it exactly like that.

LikeLike

You writing is maturing, mine in equal measure (and in a looking-glass fantasy-constructing response) – here devolves into a meaningless Zen sushi of semantic confusion.

Reflections: The fear of meaningless existence, of not leaving a ripple on the surface of the deep waters within which we swim, of decay and death without impact or attributed value from others. It is true. I suspect it is a not so stealthy nor cryptic fact of the blogging culture that other than being among other things a long-form social media experience, this is where we may suspend our disbelief in the existential void we suspect to be lurking behind appearances, where we come to weave beautiful semantic tapestries and admire (like a fish to a dancing, sparkling lure) the minds we are and the vocabularies and mental worlds we share; the rich creative realities we have woven (like some meta-mathematical enigma or material world conjured from pure axiom and logic) out of the pure nothingness of this void.

Echo fell in love with Narcissus and was rejected, forced to observe Narcissus wither and die. Echo had earlier been cursed to repeat whatever was said to her, endlessly mirroring in words the thoughts of others in her own voice. Mirrors, echoes, reflections, refractions, recursions. We all ache for recognition, largely for its own sake and surely in some respects (and as ever) the mythological archetype is instructional. I can love a mind and its thoughts and see in them the beautiful, impossibly beautiful, tragedy of all of us (I do not need to know the person behind those thoughts as our words and vocabularies are always already semantically free-floating and imaginary, like our own identities – we love that promise of potential impact); left staring into the waters and withering as time and the obscurity of historical depth claim us all (along with all of our ideas and shared almost musical, harmonies and dissonances). I am left here with the empty-sounding, meaningless phonemes of my communicative failure.

What do I mean ? Does it actually matter ? I am Narcissus and I am Echo. I am Echo. As are you, in both regards – duplicated, repeated, reiterated. Your validation returns to you through the mirrored volition of my linguistic participation, translation and metamorphosis of what you have written, my validation comes to me through writing, through my participatory existence in the shared meanings and non-meanings of all of this. One mirror turns to face another and in the act of reflection (of nothing in particular) gives flight to an imaginary depth. Echoes, flowers, river’s edges and the fish which wriggle and writhe below the surface… if I fail to capture the meaning, to attain it and in equal measure become it – I can not be slain by it.

Eros and Thanatos… the gravitationally-bound, binary star of a desire to mean something (anything at all) and an end to all meaning. Post-truth just as easily becomes post-meaning: intelligibility or logical, semantic coherence may not be as important as is making an impression where (and when) fiction has the same significance or weight as does fact… and failing to make an impression still leaves a temporal ripple. “L’application c’est le plupart de l’intelligence” ( – Paul Verlaine). But thinking clearly does not require logic to actually mean something… having crossed this stream, discard the boat… it was never meant to actually signify anything other than choppy waters and convoluted reflections and ripples.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oops. Sorry. I tend to write free-flowing as a response to other writing I encounter and to not actually post but keep the words&ideas for other things. That was unpolished. Apologies – I was very tired at the time. I shouldn’t have sent that. I enjoy your writing very much.

LikeLike

Hey, I am only quiet cos I am preoccupied with a sick cat (explain after). I don’t get offended at people’s opinions 🙂 I will respond when I can focus again!

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙂 I genuinely hope your cat gets better. Cats are beautiful creatures. It is no surprise the Egyptians worshipped them as gods. I find the symmetry of tigers to be truly mesmerising. I am still learning appropriate etiquette for this information medium. Thanks.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks. I read your long message. I don’t disagree with you, it’s just that from a psychological, rather than a philosophical, point of view, to believe that there’s meaning is important I believe.

I am not talking about universal meaning. I am talking about one’s attitude to the value of their own life – if that makes sense?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes. I understand. Personal subjectivity, purposeful existence requires meaning. The mind generates, fabricates, constructs meaning – even where there is none. Psychological meaning, attributed structure and taxonomies of significance or value allow for us to project intelligibility into/upon our experience of reality. Perhaps a great fear we all possess is that we may discover that the Universal void of meaning invalidates the existential security blanket provided by personal, subjective meaning ?

LikeLike

Your opening quote seems true to a person who has imbibed much literature but for ordinary people I don’t think the topic of the meaning of their lives would ever come up were it not for the promises of clerics. In William Manchester’s brilliant little book, A World Lit Only by Fire, he describes the lives of medieval Brits, at least the ordinary lives, when they were left to their own devices unbrutalized but eith foreign or domestic elites.

They got up every day and worked. Their lives were determined by the rhythms of the seasons and the weather and luck. In their lives animals died often enough and people, even in small villages died, too. I suspect that the idea of the meaning of one’s live ever occurred to any of them unprompted. Can you imaging a sweating farmer out hand scything a wheat field stop and ask the people around him “But what’s it all about? in a plaintive voice.

It is only the wealthy who bathe in arrogance insist that their life (so much better, you know than the peasants, yuge!) must mean something. And of course, clerics exist to suck wealth from the rich, so were there to cater to their need.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think there is a hierarchy of needs, absolutely. You know, I am very familiar with some people who still have this lifestyle in Ireland. They get up at 6 am to milk, go to bed at midnight. I think they do indeed wonder about the meaning of it all. It’s the auld lad in the pub having a pint on a Sunday that will have the most existential conversation you’ll ever have, not the wealthy you talk about.

I once was looking after a 100 year old man with a pneumonia. He was one of those hardy labourers all of his life. He had the sort of resolute calmness that you would expect of a philosopher. So I don’t think philosophy is the jurisdiction of the rich.

Maybe I am wrong, but I don’t see the rich and the poor that differently. I think in the West, we have this attitude that the poor don’t have the same insight, can’t make decision as well, etc. I think they have different pressures for sure, but I really don’t think that this condescending attitude to the poor has any reason to exist.

Maybe I am addressing a different point to what you brought up?

LikeLiked by 1 person

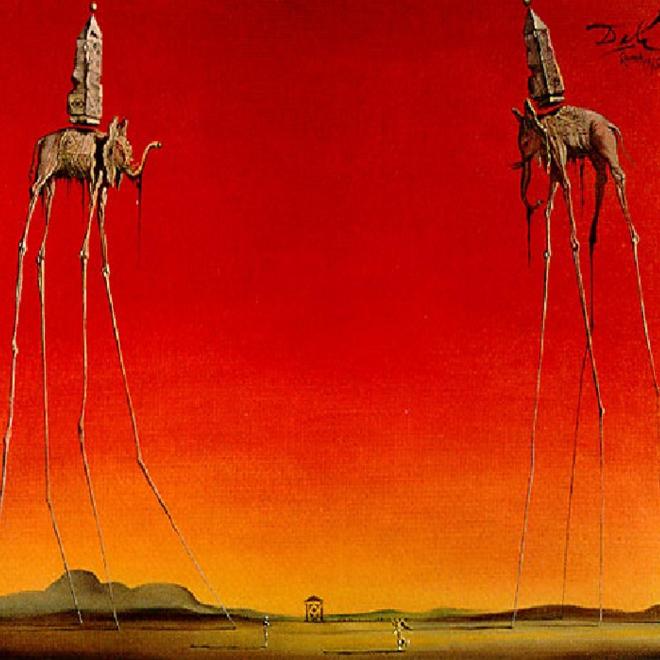

Of course I love Dali. And the Chronophobia concept is known, though the term is not one I’ve been familiar with.

We’re at different poles of life, you and I. I turn 64 about midyear 2017. Though I don’t think I’ve ever been a ‘looking back’ kind of gal. I’m both a philosopher at heart and a wicked realist. If I make a decision, I live with the consequences, simple as that. Maybe *next* time I’ll make a different choice, take Frost’s alternate path, but for now, I’ve got to deal with the fallout of that choice and learn more about myself in the process, further recognizing how form follows intention. I don’t for sure wonder about the Mars bar 😉 I don’t like the anxiety that regret puts in motion, so acceptance seems a better path, for me.

I do think we all hum with an existential fear of death to one degree or another. Personally I’m a fan of Sitting Bull’s, “It’s a good day to die.” Take life in the moment, respond to life as fully in that moment as possible. Be ready for anything without being hypervigilant. This also defines mindfulness. I think if one can be mindful all the time, it tends to eliminate regret and the past/future meanderings of a mind in overdrive.

Aloha, Martina. Well written and provocative post! ❤

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wish I was a chill as that 🙂 And as present. It’s a work in progress.

Perhaps, for me it is a form of learning – I always try to put the consequences of the choice I made into the context of what could have been. I always ask: what can I learn from this choice so as to make a better choice next time?

I think our whole lives are a string of choices, so I feel a lot of pressure. I probably also overestimate the extent to which we have control over the consequences. I think there’s the trap of “overdefining” what one can learn from any situation – and I sometimes fall right into it.

I think you’re right about the danger of being overly preoccupied with the past and the future. It’s not a new lesson for me, but it seems to need constant reinforcement.

Thanks for your kind comment as always. Aloha 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, the whole Tibetan Buddhist training thing is about observing the mind and how this past/futur-ing can get us in trouble. For we reside in neither – only in the Now, this moment. In fact Eckhart Tolle’s book The Power of Now is a great read for those whose greatest challenge is in living in the present.

Cheers, Martina! And Aloha. We’re all works in progress :0)

LikeLiked by 2 people

So interesting! I’ve been debating whether to read it or not. I do kind of draw a line when it comes to the really esoteric – and Tolle seems exactly that. You should consider reviewing it 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

First, I’ve reviewed quite a few books on Amazon, but after 9 years of radio interviews with authors, I’m a bit burned out on that process 😉 Time to relax and enjoy writing creatively, these days 😉

I really think Tolle’s approach is very down to earth and not at all esoteric in the true sense of the word. If I recall correctly, he simply speaks to the power that resides in the Now -the ever present moment – without the constant tortures of past/future mind stuff. The most esoteric thing about his approach is not really that at all; rather it’s simply an existential given – we only truly Have this moment. We don’t know what is going to happen three seconds from now, though we think we have a good idea. [I doubt the Boston Marathon people thought that bomb would happen, changing their lives forever. Not in a million years were they thinking that.] And what’s passed cannot be retrieved, even for healing purposes. The mind perceives what the mind records at that time, though we can learn from history, so to speak. Yet we cannot retrieve a given moment and make different choices. Only in This moment can we do that, and even then, depending on the amount of stress we are under, we are apt to fall back on what’s familiar.

Anyhow, enough from me! Enjoy the week, Martina! Aloha.

LikeLike

Thank you for the insight Bela! I will have a look. All of what you said is so true and yet it’s like walking on a tight rope – either the future or the past seems to want to engulf us!

LikeLiked by 1 person

What of those who fear living? Perhaps its not death, in all its peace, that causes many to tremble. Death is not a mistake.

LikeLike

Yeah, recognising one’s own capability (and how it can go wrong, be misused etc) is intimidating!

LikeLike

They use to say the human brain finished all of its neural connections around 25 years of age. That age of maturity is now thought to be closer to 30 years. Obviously it varies from person to person. Looking back over my life, 30 is about the time everything started to make sense. My view of life has changed dramatically due to my experiences and further understanding of what is important. Making an impact in the life of individuals has more value than my own legacy. How I made people feel is more important than what I accomplished. How can I leave this place better than when I arrived is now my focus.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, I think now it’s pretty reliably shown that neuroplasticity (changing of neural connections) never really stops.

That’s very interesting about being 30. I am 27 now. Sometimes I look back at my 16 y.o. self and think – I thought I knew how it all worked, whereas I had only a fraction of the insight I have now. At the same time, I always wonder: what is it that I am deluded about at the moment?

I think our impact on others is our legacy, the other “legacy” is a kind of a cultural term, really.

It seems you have a very wise resolution as your focus!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I love Dali and I loved this post, thank you for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Kate 🙂 Love poems! Your dog is very cute!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bodhi is gorgeous and such a lovely heart – we have just been for a highly energising run – love your insights ✨

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dali – always a starting point. Always new every time you look – which may be why he’s praised by some, confuses others, dismissed by still others.

What if it’s all illusion and we merely dreams? Recently said we are only part of some video game – so do the choices – or worry matter..better decide before the player gets bored and puts the plug? Ah, the mystery – and misery?

(And yes, even farmers and those who work do ponder existences not just the rich – how snooty to think that)

Lovely post

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Phil 🙂 I love surrealism!

LikeLike

Dr. Martina,

Thanks for the insightful post. As someone raised in the Hindu Vedanta culture in India, mindfulness and detachment are quite familiar to me, though I’ve always struggled to put it into practice. I am two decades older than you, and death has a lot more immediacy for me, as my older relatives pass away. My biggest fear as far as I realize, is not so much my own death (as fearsome as that is) but the impending death my loved ones. But your post has given me some cause for introspection.

Also, my sympathies for the suffering of your cat. We have a cat that we are attached to. (I’m posting under a pseudonym for privacy reasons.)

Regards

LikeLiked by 2 people

I liked what you said about parents being possibly narcissists for having children. I know there’s healthy levels of narcissism and maybe the personal drive itself, the inner dialogue might be, “I’m a pretty good guy, I might be a good dad.” Rather than the more unhelpful, “Two weeks at the bar…and it’s yours.” Both do play with a higher ego, though. Don’t you think? The Mayan, were pretty civilized for their time and it was not until they found a kind of nothingness that endless wars brought. That they then turned that emptiness inward toward human sacrifice. Its a stretch but, when you get old and when you’ve done everything, you become a parent. That, is a healthy human sacrifice.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s an interesting perspective too. Narcissism is adaptive. The difficulty with it that it tends to persist once it is no longer adaptive. I am interviewing a very interesting lady with NPD at the moment, can’t wait to publish it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Could they adaptive trait be why every few years there is a different kind of media? You know, MySpace>Facebook>Twitter>Instagram. It seems to be treating the symptom than the cure

LikeLiked by 1 person