On my quest to figure out the philosophy behind mindfulness, something that I came to be interested in through a neuroscience/psychiatry angle, I came across an intriguing presence here among the philosophically inclined bloggers: Nguyên Giác. It is my pleasure to share his views on some difficult questions that have been on my mind. As this topic concerns religion, some readers may get sensitive. Please remember Aristotle: “It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.” Enter Steven.. (I try to stay silent for most of it, but alas…)

Who am I?

I’m Steven J Barker Jr., or Nguyên Giác. I share my insights at gnotruth.com. I’m always reluctant to put forward any view, but for the sake of the people like me who benefit from the formless teachings, I type words and share them on the internet. For the sake of people like me, who have been burned by modern Christian dogma, I share alternative early Christian views. For the sake of the little ones arising in this Saha Realm, I gently shine my light so that others may see.

Not forcing any particular view, but smashing all views with Nietzsche’s hammer – I am that kind of philosopher. The anti-philosopher.

A journey through religion towards mindfulness

I was introduced to Thich Nhat Hanh’s writing when I was 12. My mom saw that I was struggling with big questions. She bought me a book: “Living Buddha, Living Christ”. I had already become quite absorbed in Christian thinking, but it was starting to bring huge conflict as my intellect was developing and Christian theology makes n0 sense. It is anti-intellectual.

Thich Nhat Hanh introduced me to a new way of thinking about the teaching of Jesus. He helped me to understand my own spiritual tradition. Understanding my own spiritual tradition, I also began to understand the words of Buddha. As a child, I began to incorporate mindfulness into my daily life.

I began to understand that mundane daily life is the chess board – it’s the actual playing field – the meditation cushion is nice, but, eventually, we have to actually stand up and face the real world.

I am Buddhist. I am engaged in the practice of continual mindfulness. In Christian terms, this practice can be called ‘walking in the Kingdom as a Child’. Before I start rambling, I want to share this beautiful description of Mindfulness by Sadasiva Saccidananda (my Dhamma friend and internet ally):

Simple practice of mindfulness, awareness of anything external or internal passing before your mind-camera, culminates in awareness of awareness itself. Naturally you shall rest in the common factor of all observations: awareness itself and seeing all as awareness, as mind in mind.

Seeing all things as equal data, even your “ego” as another observable actor among others, leads to equality & equanimity.

A mindful Jesus and a non-religious Buddha

A Buddhist is one who works toward Buddho. Buddho is unfiltered, explosive and serene awareness. Awakeness. Enlightenment. A Buddhist is one who practices mindfulness. Thich Nhat Hanh likes to equate mindfulness with the Holy Spirit.

In another of my spiritual traditions. the teachings of Yeshua, or “Christianity”, this energy or experience is called Gnosis. Perfect Gnosis is Buddho. This might sound far flung, wild and/or weird, but the path to PrajnaParamita (perfection of wisdom) is as simple as following one’s own breath.

Gospel of Thomas, 3:

Yeshua said,

If your leaders tell you, “Look, the kingdom is in heaven,”

then the birds of heaven will precede you.

If they say to you, “It’s in the sea,”

then the fish will precede you.

But the kingdom is inside you and it is outside you.

When you know yourselves, then you will be known,

and you will understand that you are children of the living One.

But if you do not know yourselves,

then you dwell in poverty and you are poverty.

The above quote, from a text which is as “authentic” as any in the New Testament, has Jesus telling us to ignore televangelists with their promises of heaven.

Instead, we find him encouraging us to practice mindfulness. The simple process of Gnoing ourselves is healing: this is mindfulness.

And, this rebellious Jesus, where did he come from!? Well, obviously, the early Church wouldn’t have survived into the present if it had openly rebuked its own leaders and encouraged people on their own spiritual journey instead of conforming to its dogma. The Gospel of Thomas’ position was thoroughly attacked by the author of the Gospel of John (check out the work of Elaine Pagels). Sadly, today’s Church is founded on the belief that Jesus is totally unique – the only son of God – this is John’s position.

John abhorred Thomas’ message that we are all children and the kingdom is already here.

Gospel of Thomas, 108:

Yeshua said,

Whoever drinks from my mouth will become like me.

I myself shall become that person,

and the hidden things will be revealed to that one.

As you can tell, I’m not very stoked on John’s message. And, I am very stoked on Thomas’ (Thomas means “twin”). I understand the message.

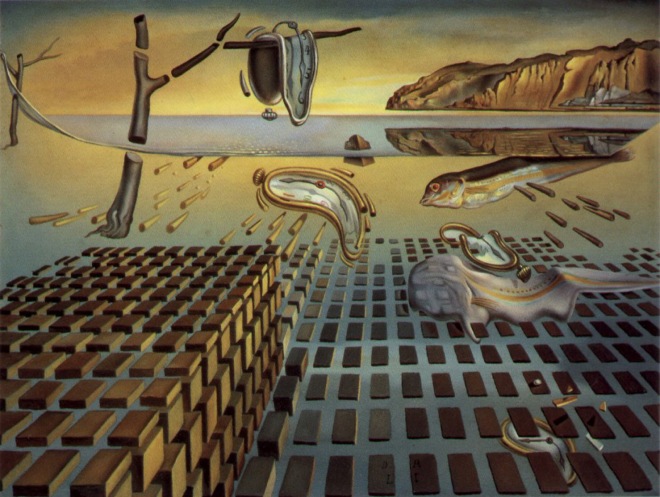

I could try to outline the process; I could try to describe the mind’s journey from ignorance and suffering to awareness, understanding and love – but this has already been done before me. There are many, many maps already – the problem is not that there aren’t enough maps, the problem is that the territory is real, alive, and changing. Old maps quickly become useless.

The ancient “map-makers” of the territory of the mind are not at fault for our foolish clinging to dead doctrine. The fault is ours.

With our fear, greed, laziness, addiction and delusion we have developed all sorts of wrong views that propagate through the mind system and create the painful errors of war, famine, disease, etc.

Gospel of Thomas, 52:

His [Yeshua’s] students said to him,

Twenty-four prophets have spoken in Israel

and they all spoke of you.

He said to them,

You have disregarded the living one among you

and have spoken of the dead.

There must be a way forward that honors the past, but also releases its grip upon our minds. We would all do well to learn to ‘philosophise with hammers’.

History of religion: a case of oversimplifying the (very) complex

History is a nice and tidy story.

History is, necessarily, always an oversimplification.

We don’t have the capacity to know this present moment in totality, so how can we hope to know the twists and turns of ephemeral ideas through rough and bloody history? I’m not saying we shouldn’t strive for historical accuracy. I’m saying we should always be skeptical of this or that narrative.

The Christian church’s “history” has been revealed to be a fabrication.

The idea that Early Christianity was one cohesive movement has been thoroughly discredited and replaced with the understanding that it was a very diverse movement with many ideas about who Jesus was and why he was important.

The same must be true about Buddhism. The West has a nice story about it’s development, but that story is just a nice summary that is most likely missing some huge pieces. I read a passage from the Encyclopedia of Religion (article by Frank Reynolds and Charles Hallisey) the other day. It boggled my mind for a bit:

“The concept of Buddhism was created about three centuries ago to identify what we now know to be a pan-Asian religious tradition that dates back some twenty-five hundred years. Although the concept, rather recent and European in origin, had gradually, if sometimes begrudgingly, received global acceptance, there is still no consensus about its definition.”

“Buddhism” is, in many ways, a European idea! Interacting with the actual cultures that practice Buddhism, you quickly find that their practice is not what you expected- it is not what you read about. Sure, there are lots of familiar things that we Europeans have accurately portrayed, but the pulsing reality of Buddhism in practice is always different from any explanation of it. It is the practice that goes beyond, beyond all thought, beyond all concepts – this practice simply cannot be made into a system. All such systems are merely hindrances.

In short, Buddhism’s history is complex and frequently oversimplified.

In the West, we have this idea of a singular Buddhism that puts forth one coherent message. However, in truth, there are many Buddhist schools and traditions with various stances on all sorts of weird issues.

This is why I have to stand back and redefine my Buddhism. I chase Buddho. I chase Gnosis. Wherever it arises, with whatever name, wearing whatever clothing – I chase Buddha. The big Buddha. The ineffable Buddha.

At the same time, I don’t want to disrespect the religious traditions that have nurtured my growth. I’ve benefited from the support of a Vietnamese Buddhist community. Taking the five precepts, becoming an “official lay Buddhist”, I received the name “Nguyên Giác”. It means something like, “awakened source” or “source of awakening”. If you like labels, you could say that I practice a mixture of Zen, Pureland and Yeshua Buddhism.

I was not raised in a “religious household”, but for whatever reason, even in my earliest memories, “religious” issues have always been extremely important to me. I did attend a Lutheran Church when I was young. I’ve read the Bible many times over and have dug through all sorts of academic papers that analyse the larger cultural context of early Christianity. I’ve spent a lot of time comparing and contrasting the texts that arose over the course of Christianity’s evolution. It has been fun and challenging. As a child of the West, the figure of Jesus has played a huge role in my development. Jesus has been with me – as both irritant and as comforter.

Gospel of Thomas:

Yeshua said,

Seek and do not stop seeking until you find.

When you find, you will be troubled.

When you are troubled,

you will marvel and rule over all.

Marvelling is a wonderful practice. I think marvelling could be classified as a type of mindfulness meditation.

There have been experiences that have revealed ‘deep’ things that are difficult to put into words. Putting words to these types of experiences, if not done with extreme care, can be harmful to oneself and to those who hear. So, instead of pointing at the goal of supreme Gnosis, I try to point at the path of mindfulness. It is something everyone can see and touch. The biggest truths cannot be conveyed with words: mind-to-mind is the only way. Set on the path of marvelling, an individual will find their own way by following beacons of joy.