I don’t really use guided meditations anymore. They get little “interrupty” after a while. I am at that point now that in any troubling situation, my mind goes straight to mindfulness. Tired? Mindfulness. Don’t know what to do next? Mindfulness. Want to check email for the 25th time today? Mindfulness. I don’t mean a full on session with all the (unnecessary) bells and whistles – I mean taking a few minutes to ground myself in the situation through conventional mindfulness techniques – breathing is a good one for me. I’m not giving up this habit any time soon.

Having said all this, I would consider guided meditations the best starting point to get into mindfulness. Most of these are free or have a free trial. Here are some recommendations:

1. Relaxing visualisation

This relaxing visualisation to bring stress levels down is narrated by a very talented practicing clinical psychologist from Trinity College Dublin Angie McLoughlin. It’s free and a good place to start. It get you to visualise a place you like. Angie speaks in a, I don’t know, Scottish or maybe Northern Irish accent? Showing my ignorance here. She trained in San Francisco, and so

I am primed to always think of the San Fran Pacific coast and sitting under a pine tree in Presidio when I listed to it.

This grounding exercise for anxiety is also narrated by Angie. More suitable for acute stress.

2. Headspace

Headspace: there’s a free trial that then leads into a subscription at about 70 euro per year. This app sends push notifications to practice for 10 minutes a day. It has some animations. The meditations are a little bit too preachy for my liking: it is almost like the narrator is trying to sell the concept. “You will feel the benefit of x, y, z…”

I found the animation about taming one’s mind like a horse by tying it to a stake using a long rope and shortening the rope every day disturbing.

I think their analogies are a little too crude, but to be fair they probably have been able to reach more people that way. It’s narrated by a man in a British accent.

3. Calm

Calm. Calm and Headspace are direct competitors. Calm is marginally cheaper. The difference is that Calm has no animations and is more psychology-driven. For example,

the narrator would deconstruct the beliefs that often underlie stress and anxiety – or goes through the cognitive processes behind judgement and self-esteem.

It’s more intelligent and less preachy than Headspace. It’s narrated by a woman in an American accent. The exact intonations are a little bit overemphatic at times – but that’s probably just an American thing. There are also a ton of “soothing ocean sound” type settings that can be nice on occasion as a kind of white noise that somehow automatically leads to more present moment awareness. I found it easier to stick with Calm than Headspace because it goes into the reasons behind feelings, allowing for relevant questions and insights.

4. Tara Brach

Tara Brach is a bit of a meditation-guru. She brings the whole Buddhist vibe in – if you’re into that. I once heard her story – it is very interesting. A few dodgy things happened to her at the hands of yogis, but she didn’t run away. For me, Buddhism is endlessly interesting but not something I want to commit to. If you are different, Tara will be great for you.

She has a very gentle manner and doesn’t take herself very seriously, which is so endearing.

I’ve never met her, but I imagine that if I did, it would completely change how I felt for the day. She kind of radiates this feminine loving-kindness-acceptance vibe. She speaks in a very non-grating American accent.

5. UCLA

UCLA Mindful Awareness Research Center meditations are free and complete.

UCLA probably cover the lion’s share of what Calm and Headspace cover – but they are less personable.

They are more clinical, kind of like the safety instruction on a plane. They are narrated by a woman in an American accent. They are also available in Spanish.

There a lot of meditations on YouTube. I’ve bumped into a few too many dodgy ones, so I would recommend sticking with the tried and tested above.

6. Simple Habit

Simple Habit is much like Calm. However, it is 5 minutes every time. There are a variety of speakers and styles, so it’s a great starting point.

For the sake of balance, I include this FT article that reflects the limitations of mindfulness apps. Apps and internet resources are a great starting point. However, really, it’s not just a ritual. It’s about being in the moment in our daily lives.

You may also like:

Beginner mistakes in mindfulness and how to avoid them

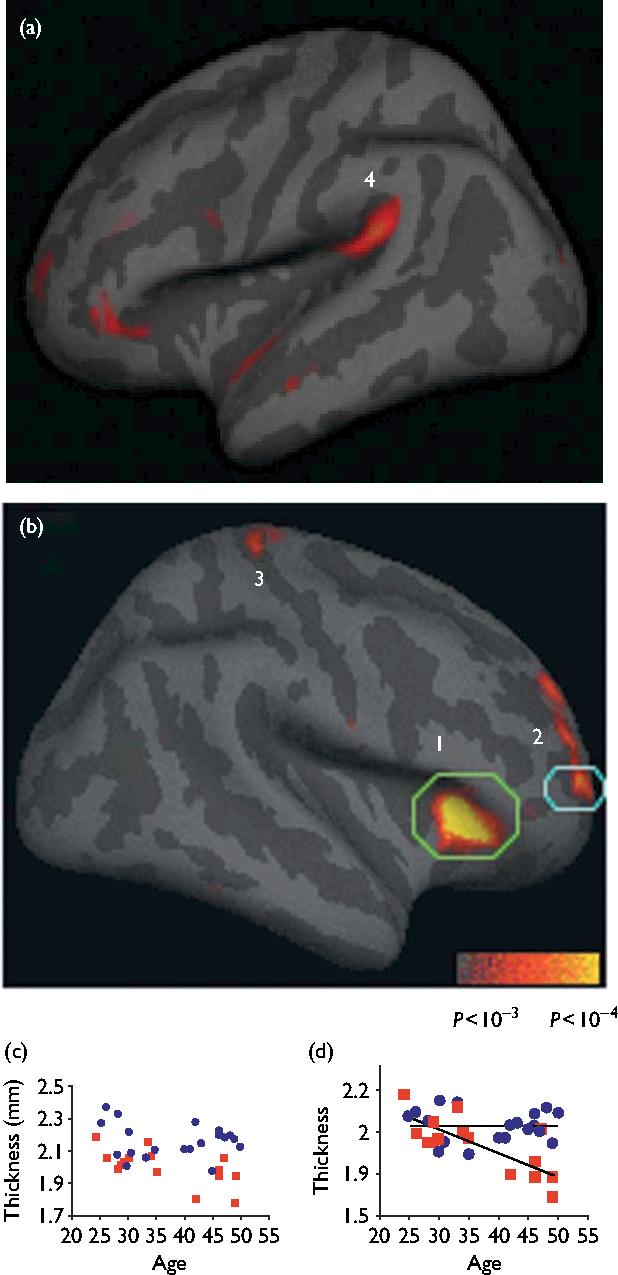

Mindfulness changes brain structure