The positive thinking crowd – who have flooded every corner of the internet, most of all social media, would have us believe that our minds instinctively drive us towards that which we focus on. Hence, it makes sense to focus on the good, according to them.

As a naturally skeptical-yet-optimistic person, I find myself repelled by the cult of positivity. Below, I explain the theory behind positive thinking and the reasons why it ultimately doesn’t work.

There is logic behind positivity. For example, attentional bias and its many cousins are our way of noticing the things we prefer to notice even more.

So if we try to notice good things, we are likely to notice a disproportionate amount of good things. It is assumed that by being surrounded by positivity, we will feed off this virtuous cycle and gather the strength to produce other good things. Another argument in defence of positive thinking is that our brains tend to follow certain patterns, habits of sorts. Feeling good more often leads to more feeling good. Another virtuous cycle.

Positive thinkers encourage setting and identifying with ambitious goals as a necessary part of all achievement in life. There are endless quotes from celebrity icons to support this. Many of those who have succeeded would say – I had a vision of x, y, z – and here I am now, I’ve achieved it.

We don’t hear the, undoubtedly, innumerable stories of those who go through the same “law of attraction” process – without ever arriving at their destination.

In addition, we’re quick to assume a causal relationship between the idiosyncrasies of the successful and their success. These are just two of many biases that are inherent in the positive thinking logic. So of what value is this obsession with studying the habits of the ultra-successful? As role models – fair enough. However,

the studies that support positive thinking are more often than not obviously in violation of basic parts of the scientific method.

But hey, it takes a while to prove anything, so we will bear with them for now.

By that same positive thinking logic, thinking about negative things will somehow lead to these bad things. Good point (we will agree with their assumptions for now). There is one problem with it though. Let me explain.

Forcing ourselves to focus on the good things creates a kind of dissonance. One part of our brains is saying: we should feel positive in all circumstances. Another part of our brain is pointing out all the things that we are used to feeling bad about.

Now, it is possible that the way we are interpreting the world is unhelpful, but this requires a lot of work to unmask and change. Therefore, until the hard work of rethinking our beliefs, for example, through the (much more) scientifically backed talk therapy is at least attempted, it is impossible to cure the feeling that something is off kilter in our heads as a consequence of positive thinking. It feels fraudulent and may even make the subject feel worse. Furthermore – and this is the interesting part – this sensation of something not being right will draw more attention to these negative thoughts we were told to run from.

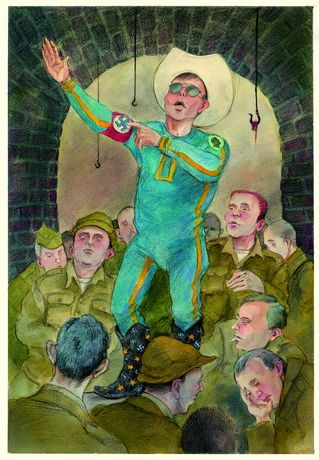

The swollen positivity of Instagram’s motivational gurus doesn’t just urge us to be positive – it tells us that being negative is wrong.

“Rid your life of negative people”. “Purge negative words from your vocabulary”. “Avoid negative thoughts”. Forcing positivity accentuates negativity: whenever we feel down we will flag it as red, pumped by inspirational quotes. So positive thinking urges us to focus on the negative. Isn’t this negative focus going to lead to negative events – by their own logic? In addition,

the red-flagging of negative thoughts often results in further guilt and helplessness to go with our already negative feelings.

There is another problem with telling people not to think stuff. It was voiced by Fedor Dostoyevsky, a hero of mine since back in school when I managed to write an exam essay outlining the importance of the religion in Crime and Punishment that was corrected by a 70 year old Soviet-through-and-through teacher of literature – resulting in a stellar grade. Fedor gets the credit here. Anyway! He said that the things that we try to not think about are the very things we end up thinking about.

Could you do me a favour and not think of a blue scarf please?

Yeah, I know.

Furthermore, telling someone how they should feel is fertile ground for tyrannies of the shoulds – feeling low as a consequence of now complying with some preconceived rule, or should. More unintended negativity.

This emphasis on avoiding negativity draws us no less to negative events than the focus on positivity draws us to positive events

…I hypothesise. In addition, the dissonance and a new rule to follow about something only partially under our control in and of themselves feels rotten, i.e. more negative feelings.

I think positive thinking is flawed: not because it has no basis, but because its basis has counterweights that accentuate the negative thoughts just as much – made worse by the uncomfortable dissonance it creates. It just makes us judge our thoughts more.

Don’t get me wrong, I don’t think that allowing ourselves to ruminate on sad things we cannot change, having no faith in ourselves or any other unhelpful behaviour should be encouraged to spite the positive thinkers of the self-help industry. I just don’t believe positive thinking is going to solve the underlying conflicts. It is a good idea to see the best in people and things etc. It is a good idea to let our positivity strengthen. It just can’t be compulsive – or the positive effect is ruined as described above.

There’s no need to dwell on the negative beyond what is reasonable either. For example, raising awareness about suicide sometimes results in a higher incidence of it. Not dwelling on something can be achieved without running from it, however.

There is a nice point on the emotional “graph” – and I think we could reach it by being a bit more open-minded about the negative.

It makes sense to reflect on this through the most extreme negative thought – of death. Being comfortable with the thought of death seems preposterous to most people – unless they are a doctor or something like that. Even then – it’s not their own death they are thinking about. When I first heard of the annual Mexican festival in celebration of death, it seemed insane – blasphemous in a kind of secular way. My own mother, who unlike me did not grow up with Halloween, still feels there’s something not quite right about it. People in our culture seem to avoid thinking about death as if somehow thinking about it will bring it closer.

Where do positive thinkers stand on death? Is thinking of death banned as well? It would seem obvious that death is regarded as one of the worst possible outcomes in our culture. Well, ok, but it’s going to happen anyway. The theory underlying positive thinking would lead us to believe that thinking of death will somehow bring it closer. The thought of our own mortality cannot be easily tolerated. It has to go right now. We may touch wood or bless ourselves to undo the damage it already caused. Obviously, there are other explanations for this besides what we usually call positive thinking, but the mechanism is the same. We just don’t want to bring it upon ourselves.

So is it ok to talk about death yet? The Mexicans are a pretty happy people, or so they say in those country-by-country happiness studies. Death was a beloved subject of the medieval tradition – with their skulls on their tables in countless paintings to remind themselves of death.

There are many lessons to be derived from thinking of death.

The Stoics loved thinking of death – it’s their way to remind themselves that nothing is worse than death – and death isn’t that bad. It’s our beliefs about it that make it bad. Hence, there is no need to fear death. Since we don’t have to fear death – the worst outcome of all, surely, we don’t have to fear anything else. Buddhists would regard death as just another experience – neither good nor bad.

Maybe that’s it: it’s all about trying to avoid uncertainty – “the thought of undiscovered country from whose bourne/ No traveller returns, puzzles the will”. Positive thinking seems to heal the pain of uncertainty.

It positively confuses our brains – that aren’t very good at distinguishing between fantasies and reality to begin with. One of the proposed benefits of positive thinking is that it gives us a sense of certainty. It is argued then that once we believe that something is indeed possible, we will find it easier to achieve it. That’s why it’s so popular: it eases the fear of uncertainty.

Besides being told to think positively, could there be other reasons why we dislike thinking about death so much then – given that is, well, as good as certain? The facts may be the facts, but way we think about death is full of uncertainty. In the extreme, there is a part of each of us that isn’t quite certain that we will die: it will be an older me, a more prepared me, not me me. Maybe; but seeing as how at 27 I don’t feel radically different to how I felt when I was half that age, I imagine it will be me me. However, just like the minus infinity to 1989, the infinity that I will miss out on after I am gone is just a part of what we got into when we were born. We also have no idea what will happen when we die – if anything, adding to the dreaded uncertainty. As evidenced by the scanty insights brought up here though: there is much to learn by thinking of the seemingly negative.

It would be mean to get to this point and not offer some kind of alternative to the wretched positive thinking. My answer, as much as it is possible to answer, is giving up on the hatred of uncertainty. There will always be uncertainty. No amount of meaningful relationships or possessions will ever shield us from uncertainty. We probably should set goals, but not cling to them unaware of the changing world around us. We can try and tame uncertainty by working around it, by forming beliefs that aren’t sabotaged by uncertainty – but not by resisting it through compulsive meaningless positive thinking.