“Most history is guessing, and the rest is prejudice”

Will and Ariel Durant

I have a strong feeling that I shouldn’t be a fan of a hedge fund guy who married a Vanderbilt, but Ray Dalio is a really interesting person. He’s arguably the worlds most successful hedge fund manager. The average hedge fund lasts 18 months; his Bridgewater is 42 years old as of 2017. He is an avid meditator of the transcendental/Beatles variety. He’s also a warm and fuzzy ENTP. Lol jk, as they say.

I read his Principles a while ago. They make a lot of sense. The name is obviously quite aspirational and part so the opus are quite philosophical. I am sure that Dalio chose it with posterity in mind. At some point, he answered the question, “What is the best book you’ve ever read?” with a definitive The Lessons of History by Will and Ariel Durant, 1968.

It’s a short, captivatingly well-written book. W&A really don’t mince their words (except in the last chapter on whether progress is real). While their opening chapter is called Hesitations, it’s pretty definitive:

As his studies come to a close, the historian faces the challenge: Of what use have your studies been? Have you found in your work only the amusement of recounting the rise and fall of nation, and retelling “sad stories of the death of kings”?

Don’t you just want to read on? History was almost ruined for me as a discipline back when I was in school – and this book revived it. At the time, I found that the book was very difficult to get, so I ended up requesting it from stacks in a copyright library of Trinity College Dublin. Here it is now, thank you Jeff Bezos: The Lessons of History.

Really, the purpose of the book is to use history as the study of human nature:

Since man is a moment in astronomic time, a transient guest of the earth, a spore of his species, a scion of his race, a composite of body,character, and mind, a member of a family and a community, a believer or doubter of a faith, a unit in an economy, perhaps a citizen in a state or a soldier in an army, we may ask under the corresponding heads – astronomy, geology, geography, biology, ethnology, psychology, morality, religion, economics, politics, and war-what history has to say about the nature, conduct, and prospects of man.

It has this Art of War quality to it, only it makes more sense. Here are my “underlines” of the superb and oftentimes controversial views of the Durants:

- Known history shows little alteration in the conduct of mankind. The Greeks of Plato’s time behaved very much like the French of modern centuries; and the Romans behaved like the English.

- Inequality is not only natural and inborn, it grows with the complexity of civilization. Hereditary inequalities breed social and artificial inequalities; every invention or discovery is made or seized by the exceptional individual, and makes the strong stronger, the weak relatively weaker, than before.

- Nature smiles at the union of freedom and equality in our utopias. For freedom and equality are sworn and everlasting enemies, and when one prevails the other dies.

- “Racial” antipathies have some roots in ethnic origin, but they are also generated, perhaps predominantly, by differences of acquired culture-of language, dress, habits, morals, or religion. There is no cure for such antipathies except a broadened education. A knowledge of history may teach us that civilization is a co-operative product, that nearly all peoples have contributed to it; it is our common heritage and debt; and the civilized soul will reveal itself in treating every man or woman, however lowly, as a representative of one of these creative and contributory groups.

- Intellect is a vital force in history, but it can also be a dissolvent and destructive power. Out of every hundred new ideas ninety-nine or more will probably be inferior to the traditional responses which they propose to replace. No one man, however brilliant or well-informed, can come in one lifetime to such fullness of understanding as to safely judge and dismiss the customs or institutions of his society, for these are the wisdom of generations after centuries of experiment in the laboratory of history.

- The conservative who resists change is as valuable as the radical who proposes it-perhaps as much more valuable as roots are more vital than grafts. It is good that new ideas should be heard, for the sake of the few that can be used; but it is also good that new ideas should be compelled to go through the mill of objection, opposition, and contumely; this is the trial heat which innovations must survive before being allowed to enter the human race.

- History offers some consolation by reminding us that sin has flourished in every age. Even our generation has not yet rivalled the popularity of homosexualism in ancient Greece or Rome or Renaissance Italy.” Prostitution has been perennial and universal, from the state-regulated brothels of Assyria to the “night clubs” of West-European and American cities today. In the University of Wittenberg in 1544, according to Luther, “the race of girls is getting bold, and run after the fellows into their rooms and chambers and wherever they can, and offer them their free love.” Montaigne tells us that in his time (1533-92) obscene literature found a ready market, the immorality of our stage differs in kind rather than degree from that of Restoration England; and John Cleland’s Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure -a veritable catena of coitus-was as popular in 1749 as in 1965.

- We must remind ourselves again that history as usually written is quite different from history as usually lived: the historian records the exceptional because it is interesting-because it is exceptional.

- The influence of geographic factors diminishes as technology grows. The character and contour of a terrain may offer opportunities for agriculture, mining, or trade, but only the imagination and initiative of leaders, and the hardy industry of followers, can transform the possibilities into fact; and only a similar combination (as in Israel today) can make a culture take form over a thousand natural obstacles. Man, not the earth, makes civilization.

- History has justified the Church in the belief that the masses of mankind desire a religion rich in miracle, mystery, and myth. Some minor modifications have been allowed in ritual, in ecclesiastical costume, and in episcopal authority; but the Church dares not alter the doctrines that reason smiles at, for such changes would offend and disillusion the millions whose hopes have been tied to inspiring and consolatory imaginations.

- There is no significant example in history, before our time, of a society successfully maintaining moral life without the aid of religion.

- History reports that “the men who can manage men manage the men who can manage only things, and the men who can manage money manage all”. From the Medici of Florence and the Fuggers of Augsburg to the Rothschilds of Paris and London and the Morgans of New York, bankers have sat in the councils of governments, financing wars and popes, and occasionally sparking a revolution. Perhaps it is one secret of their power that, having studied the fluctuations of prices, they know that history is inflationary, and that money is the last thing a wise man will hoard.

- The experience of the past leaves little doubt that every economic system must sooner or later rely upon some form of the profit motive to stir individuals and groups to productivity. Substitutes like slavery, police supervision, or ideological enthusiasm prove too unproductive, too expensive, or too transient.

- The concentration of wealth is natural and inevitable, and is periodically alleviated by violent or peaceable partial redistribution. In this view all economic history is the slow heartbeat of the social organism, a vast systole and diastole of concentrating wealth and compulsive recirculation.

- The fear of capitalism has compelled socialism to widen freedom, and the fear of socialism has compelled capitalism to increase equality.

- Alexander Pope thought that only a fool would dispute over forms of government. History has a good word to say for all of them, and for government in general. Since men love freedom, and the freedom of individuals in society requires some regulation of conduct, the first condition of freedom is its limitation; make it absolute and it dies in chaos.

- Since wealth is an order and procedure of production and exchange rather than an accumulation of (mostly perishable) goods, and is a trust (the “credit system”) in men and institutions rather than in the intrinsic value of paper money or checks, violent revolutions do not so much redistribute wealth as destroy it.

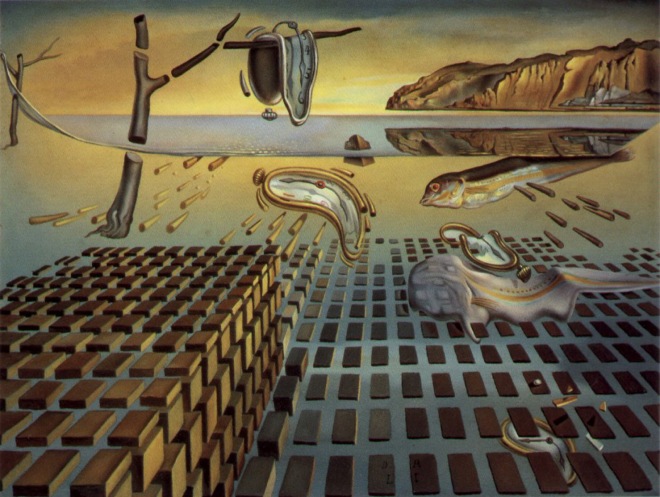

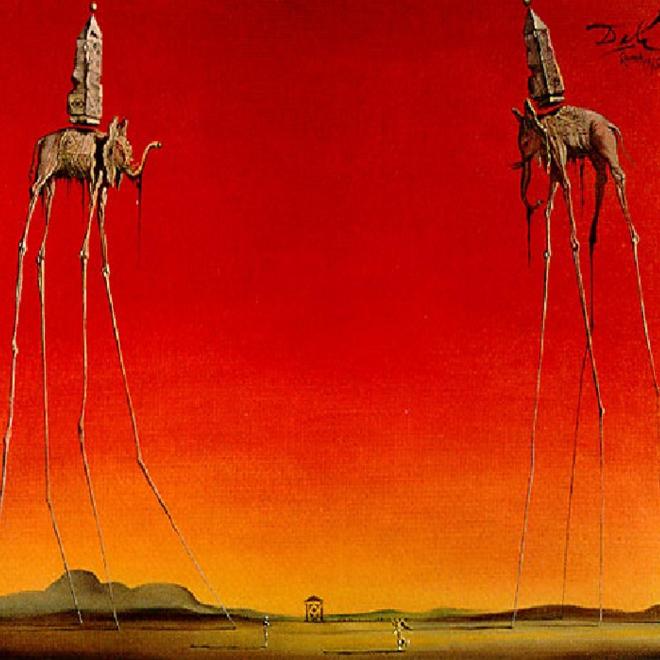

- Is democracy responsible for the current debasement of art? The debasement, of course, is not unquestioned; it is a matter of subjective judgment; and those of us who shudder at its excesses-its meaningless blotches of color, its collages of debris, its Babels of cacophony – are doubtless imprisoned in our past and dull to the courage of experiment. The producers of such nonsense are appealing not to the general public – which scorns them as lunatics, degenerates, or charlatans – but to gullible middle – class purchasers who are hypnotized by auctioneers and are thrilled by the new, however deformed.

- No student takes seriously the seventeenth-century notion that states arose out of a “social contract” among individuals or between the people and a ruler. Probably most states (i.e., societies politically organized) took form through the conquest of one group by another, and the establishment of a continuing force over the conquered by the conqueror; his decrees were their first laws; and these, added to the customs of the people, created a new social order.

- When the group or a civilization declines, it is through no mystic limitation of a corporate life, but through the failure of its political or intellectual leaders to meet the challenges of change.

On the subject of the necessity of stupid work:

On the subject of the necessity of stupid work: