Shortly after I finished my medical degree, I pursued a master’s degree in finance. The 2008 market crash was pretty terrible for Ireland – and I was curious to find out get out of the medical bubble and learn about the world. After 5 years of medicine, everyone who wasn’t a doctor seemed well-rounded, but one of the most well-rounded wonderful friends I made during that masters suggested that I read Principles by Ray Dalio back in the day.

Dalio is the founder of (probably) the most successful hedge fund. Unlike all those 10-steps-to-success type books by various billionaires, Principles lacks the motivational element and has lots of cold rational logic. I found it to be a fascinating read.

You will find lots of free pdf copies of Principles online. The paid (expanded) version is a recent development. The book was in open access for years. The fact that it’s free is one of the things that made it different to books written by the likes of Richard Branson. I wonder what Dalio is up to with the paid version. The capitalist in him must be rebelling against giving out free stuff, I guess…

More recently, Dalio mentioned that reading Ayn Rand would be key to understanding the mindset of Trump era economics and politics. I poked around a few articles about Rand and was surprised to find that her philosophy was rejected by critics and academics. I’d never heard of these words in the same sentence. What does it mean to reject a philosophy? Turning to a family member beside me with this naive question, I received a less than naive answer: it is a situation where a philosophy isn’t politically expedient. Oh dear.

Nevertheless, her thoughts reminded me of Nietzsche. I don’t think he spoke about economics very much, but if he had, I am sure he would have said exactly what Rand had to say.

So I started with Atlas Shrugged.

Is Atlas Shrugged a pleasant read?

Just like Brave New World, Atlas Shrugged a philosophical book dressed up as a novel. For the more analytical among us, it’s definitely a stimulating read. The characters are a little flat and improbable, but that’s just the nature of these type of works. A few cringy sex scenes. A touch of naive feminism.

Rand writes in impossibly long sentences and can seem excessively intellectual-for-the-sake-of-being-intellectual. Over 1,000 pages of that can get tiring.

Is Atlas Shrugged a worthwhile read?

The book addresses some issues we face today in the West in a way that nobody would ever dare in this day and age. We can barely take a breath without getting a licence, insurance and paying tax on it. We’re not actually free to speak our mind out here, even though we pride ourselves on it. There has been a lot of violence in US universities against right wing groups citing social justice as a legitimate justification.

In such a world, Rand’s writing is a breath of fresh air – but not for long. The discerning reader soon realises that Rand painted an impossible utopia, just like the communists she so hates, and that she is simply wrong in many of her sweeping statements.

What’s Atlas Shrugged about?

It’s about a (slightly) dystopian United States with a touch of sci fi. Prepare for a lot of talk about railways, oil, steel and trains. A government nationalises the major corporations in a fever of extorting socialism. You can hazard a guess where she got her inspiration.

Who is Ayn Rand?

She was an atheist woman of Russian Jewish bourgeoisie origins. As a 20 year old, she left the USSR and settled in the US. Interestingly, she became an atheist before it was cool strongly recommended by the Soviets. Her father was a businessman. He was stripped of his fortune during the Revolution of 1917. Legend has it that the first book she purchased in the US was Thus spoke Zarathustra.

Incidentally, it is thought that she is an INTJ, so our ENTP crowd are likely to like her style.

What did Ayn Rand believe?

1. Rand believed that religion and socialism are evil

Rand isn’t just against religion, she believes that socialists are basically Religion 2.0.

Both [religion and socialism] demand the surrender of your mind, one to their revelations, the other to their reflexes. No matter how loudly they posture in the roles of irreconcilable antagonists, their moral codes are alike, and so are their aims: in matter—the enslavement of man’s body, in spirit—the destruction of his mind.

Neither religion nor socialism welcome questioning:

The purpose of man’s life, say both, is to become an abject zombie who serves a purpose he does not know, for reasons he is not to question… Both kinds demand that you invalidate your own consciousness and surrender yourself into their power.

2. Rand rejected true world theories

Although Rand herself said “The only philosophical debt I can acknowledge is to Aristotle”, this is more or less straight out of Nietzsche:

[Religion and socialism] claim that they perceive a mode of being superior to your existence on this earth. The mystics of spirit call it ‘another dimension,’ which consists of denying dimensions. The mystics of muscle call it ‘the future,’ which consists of denying the present.

3. Rand thought that reality and perception are completely separate

Shakespeare said that nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so. Rand begs to differ:

They want to cheat the axiom of existence and consciousness, they want their consciousness to be an instrument not of perceiving but of creating existence, and existence to be not the object but the subject of their consciousness—they want to be that God they created in their image and likeness, who creates a universe out of a void by means of an arbitrary whim. But reality is not to be cheated.

A savage is a being who has not grasped that A is A and that reality is real.

The fact that we can perceive things that aren’t what they initially seem doesn’t take away from the separation of reality and perception:

The day when he grasps that the reflection he sees in a mirror is not a delusion, that it is real, but it is not himself, that the mirage he sees in a desert is not a delusion, that the air and the light rays that cause it are real, but it is not a city, it is a city’s reflection—the day when he grasps that he is not a passive recipient of the sensations of any given moment, that his senses do not provide him with automatic knowledge in separate snatches independent of context, but only with the material of knowledge, which his mind must learn to integrate—the day when he grasps that his senses cannot deceive him, that physical objects cannot act without causes, that his organs of perception are physical and have no volition, no power to invent or to distort, that the evidence they give him is an absolute, but his mind must learn to understand it, his mind must discover the nature, the causes, the full context of his sensory material, his mind must identify things that he perceives—that is the day of his birth as a thinker and scientist. (Note that this is all one sentence!)

4. Rand postulated that a contradiction is the marker of a mistake

A touch of Aristotle:

Contradictions do not exist. Whenever you think that you are facing a contradiction, check your premises. You will find that one of them is wrong.

Emotion that isn’t congruent with thought indicated an unresolved conflict:

An emotion that clashes with your reason, an emotion that you cannot explain or control, is only the carcass of that stale thinking which you forbade your mind to revise.

5. Rand believed that refusing to think is a crime

Much as I disagree with Rand on many points, I do agree with this:

There are no evil thoughts except one: the refusal to think.

To varying extents, we are all guilty of this – and our parents are, of making us trust authority over our own judgement:

A mystic is a man who surrendered his mind at its first encounter with the minds of others. Somewhere in the distant reaches of his childhood, when his own understanding of reality clashed with the assertions of others, with their arbitrary orders and contradictory demands, he gave in to so craven a fear of dependence that he renounced his rational faculty.

If you’ve given up on thinking, emotion is all that’s left:

From then on, afraid to think, he is left at the mercy of unidentified feelings. His feelings become his only guide, his only remnant of personal identity, he clings to them with ferocious possessiveness—and whatever thinking he does is devoted to the struggle of hiding from himself that the nature of his feelings is terror.

It’s not possible to be rational while only being rational about certain things:

Whenever you committed the evil of refusing to think and to see, of exempting from the absolute of reality some one small wish of yours, whenever you chose to say: Let me withdraw from the judgment of reason the cookies I stole, or the existence of God, let me have my one irrational whim and I will be a man of reason about all else—that was the act of subverting your consciousness, the act of corrupting your mind.

Resorting to mysticism means an inability to convince:

Every dictator is a mystic, and every mystic is a potential dictator… A mystic craves obedience from men, not their agreement.

If anyone wonders what it would be like to be Antichrist, just post the below on Instagram:

To a savage, the world is a place of unintelligible miracles where anything is possible to inanimate matter and nothing is possible to him.

6. Religion is a racket according to Rand

I went to an uber-Catholic school at one point. I recall my teacher telling me with great conviction that Jesus died for us. This thing we hear all the time is actually quite a confusing statement, so I asked why he had to die for us. The teacher proceeded to explain the concept of the original sin – and all I was thinking of, sure what have I to do with that? If forgiveness is more or less the ultimate virtue in Christianity, how come God is still holding Adam and Eve’s mischief against us? Rand seems to be of the same opinion:

The name of this monstrous absurdity is Original Sin. A sin without volition is a slap at morality and an insolent contradiction in terms: that which is outside the possibility of choice is outside the province of morality. If man is evil by birth, he has no will, no power to change it; if he has no will, he can be neither good nor evil; a robot is amoral.

Here is her summary of how religion rose to power:

For centuries, the mystics of spirit had existed by running a protection racket—by making life on earth unbearable, then charging you for consolation and relief, by forbidding all the virtues that make existence possible, then riding on the shoulders of your guilt, by declaring production and joy to be sins, then collecting blackmail from the sinners.

7. Universal basic income has no place in a Randian world

Rand is pointing out the Ponzi scheme in UBI:

They proclaim that every man born is entitled to exist without labor and, the laws of reality to the contrary notwithstanding, is entitled to receive his ‘minimum sustenance’—his food, his clothes, his shelter—with no effort on his part, as his due and his birthright. To receive it—from whom? Blank-out.

8. Decisions: make them or die, says Rand

Rand advocates extreme responsibility. It one of the main virtues to her. A person who doesn’t take responsibility doesn’t deserve to live:

Calmly and impersonally, she [the main character], who would have hesitated to fire at an animal, pulled the trigger and fired straight at the heart of a man who had wanted to exist without the responsibility of consciousness.

9. Trade is the ultimate human relationship

There is a lot of worshipping of the dollar in the book. Rand says that trade is great because it is consensual and it creates value for both parties:

Money rests on the axiom that every man is the owner of his mind and his effort. Money allows no power to prescribe the value of your effort except the voluntary choice of the man who is willing to trade you his effort in return. Money permits you to obtain for your goods and your labor that which they are worth to the men who buy them, but no more. Money permits no deals except those to mutual benefit by the unforced judgment of the traders. Money demands of you the recognition that men must work for their own benefit, not for their own injury, for their gain, not their loss—the recognition that they are not beasts of burden, born to carry the weight of your misery—that you must offer them values, not wounds—that the common bond among men is not the exchange of suffering, but the exchange of goods.

Money demands that you sell, not your weakness to men’s stupidity, but your talent to their reason; it demands that you buy, not the shoddiest they offer, but the best that your money can find. And when men live by trade—with reason, not force, as their final arbiter—it is the best product that wins, the best performance, the man of best judgment and highest ability—and the degree of a man’s productiveness is the degree of his reward.

But what about love, I hear you ask? Her views on love are all about self-interest. Ultimately, love is a deal people make.

The Randian Ubermensch:

- unconditionally loves life

- has infinite belief in himself

- is driven by intellect and self-interest

- doesn’t wallow in weakness

- takes responsibility for absolutely everything that happens to him

- does not sacrifice and takes the oath: “I swear by my life and my love of it that I will never live for the sake of another man nor ask another man to live for mine.”

Holes in Rand’s philosophy

1. Rand doesn’t address the issue of chance

Rand says:

As there can be no causeless wealth, so there can be no causeless love or any sort of causeless emotion.

There are all of these things in real life. Not for good reason, but they do exists. This is the main reason her philosophy isn’t useful: Rand doesn’t address the issue of chance.

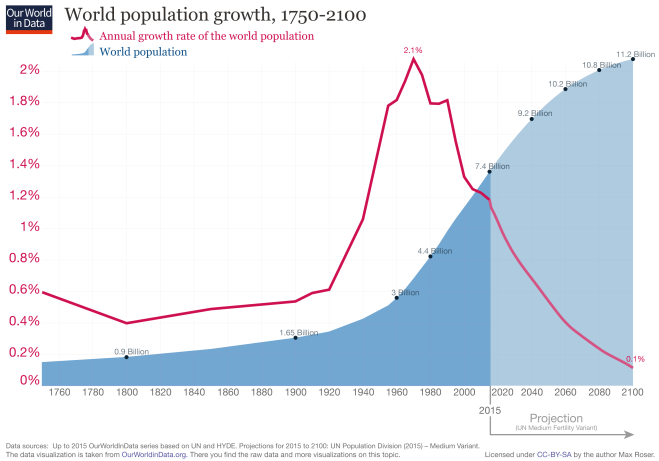

Very often people who succeed overdefine their successes (and failures). It’s almost like survivor’s guilt: “I made it because I tried. If you haven’t made it, it’s because you didn’t try hard enough.” We all know that that’s not how things are in reality. In the long term, yes, Fortune favours the bold – or so I tell myself.

Most of the main characters appear to have inherited their fortune. John Galt, the real hero of the story, the inventor of the marvellous engine, didn’t. He wouldn’t have risen to the top by inventing an engine in real life. His invention would have been coopted by the owner of the huge corporation he worked for. He would probably get a gift voucher at the Christmas party. Where is the guy who invented the internet now? “It wasn’t one person.” True. But it wasn’t one person who made computers, smartphones, Facebook or whatever – yet we can put a name to these things because someone managed to make it into their own business.

Ayn Rand opposes that horrible Soviet-like “Equalisation of Opportunity” act in her novel, but this is why her philosophy has done little to address the downsides of socialism: she doesn’t address their main concern – that chance plays a large part in one’s life.

2. Rand looks for patterns where there aren’t any

A closely related point is that Rand believes that everything can be made into science.

The links you strive to drown are causal connections. The enemy you seek to defeat is the law of causality: it permits you no miracles.

Causality is a very ambitious concept to manoeuvre with. During my study of statistics I understood that causality is all smoke and mirrors. All we have are some intuitive concepts of what causes what. There is no real way to prove causality.

Looking for patterns in randomness has always been a hobby of the human race. Rain is caused by the generous sacrifices to the goddess of agriculture in the previous years. Investment returns are caused by prior results. A successful career follows from great interview performance. No. They aren’t. Some things are just random. Rand didn’t understand that.

3. Rand rejects the idea that there are things outside of our control

…it cannot be done to you without your consent. If you permit it to be done, you deserve it.

Here is more of Rand’s blame-the-victim philosophy. In certain contexts, the above is true, but it’s not quite as black and white as Rand makes out. What if your parents are addicted to drugs and you are addicted now too. Did you deserve it? Were you wrong to trust the people who gave you life and basically were your life for a long time?

This is how people get to be neurotic in the modern world: beating themselves up for not being able to control things… that they cannot possibly control. Rand rejects the idea that there are things outside of our control.

4. Rand confuses useful assumptions and absolutes

‘We know that we know nothing,’ they chatter, blanking out the fact that they are claiming knowledge—’There are no absolutes,’ they chatter, blanking out the fact that they are uttering an absolute—’You cannot prove that you exist or that you’re conscious,’ they chatter, blanking out the fact that proof presupposes existence, consciousness and a complex chain of knowledge: the existence of something to know, of a consciousness able to know it, and of a knowledge that has learned to distinguish between such concepts as the proved and the unproved.

Socrates got a beating there. To my mind, Rand is overambitious. A reasonable human being will operate on her assumptions, but they will not take them to be the only possibility.

5. Rand forgets the darker side of trade

To trade by means of money is the code of the men of good will.

What about selling heroin, Ayn?

And, Ayn, if you don’t hire me to be your security guard, I will break your windows.

It’s not just the Church that blackmails people.

6. Rand believes we live in a meritocracy of irreplaceable minds

In Atlas Shrugged, the brightest, most industrious people escape into a hidden world one by one as their creations get nationalised. This leads to a failed state; everything comes to a stand-still. Would this happen in reality?

This assumes that we live in a meritocracy. I believe in the power of genetics more than most people, but not everyone who inherits their parent’s empire is going to be as good as them. Rand acknowledges this fact in her character Jim Taggart, but seems to imply that the best will still rise to the top.

I don’t think that the world would be quite so helpless without its aristocracy. Every significant change of power in history has led to the destruction of the previous regime’s nobility. They just kept going anyway though: new nobility found its feet pretty quickly. When Atlas gets tired, he just adjusts his grip.

7. Rand states that happiness is the purpose of life

What a nice and simple formula. Only it is as foggy as dividing by zero. What does it mean to be happy, Ayn?

What is my verdict on Rand’s philosophy?

I do agree that reality exists without our consciousness (this is the central idea of objectivism).

I admire her love of life, reality, intellect and industrious creation of value.

I think she simplified the complex and destroyed her credibility.

Her work is more of an ideology with defined values than a philosophy that helps to understand the word.