Man cannot endure his own littleness unless he can translate it into meaningfulness on the largest possible level

Ernest Becker

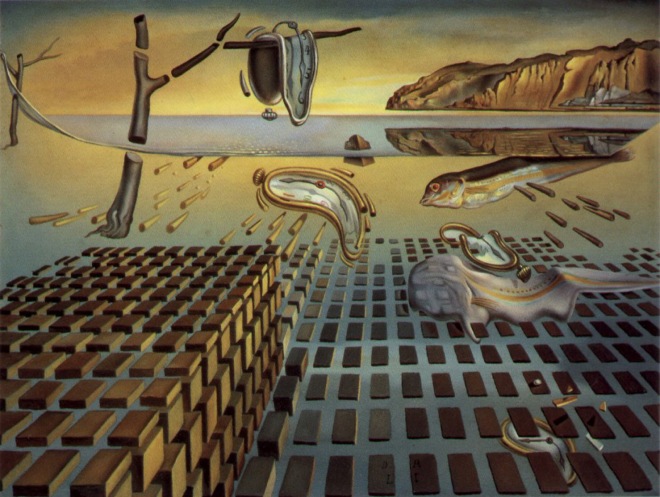

Fear of the passage of time

I recently came across the term chronophobia in the context of people doing exams: knowing that exam day is ever closer makes people anxious. Chronophobia was defined as an experience of unease and anxiety about time, a feeling that events are moving too fast and are thus hard to make sense of, in “Chronophobia: On Time in the Art of the 1960s” by Pamela Lee.

Chronophobia isn’t a formal diagnosis, neither does it feature in scientific literature. In other words, it’s not really a phobia. It is more of an unpleasant feeling – one that is often expressed in art.

It is common in prison inmates, students in long academic programs and the elderly. When one is anxious, it is not only possible to be anxious about the event, but also its inescapable approach. Chronophobia is less about the doom and more about it being impending.

Chronophobia appears to be connected with heightened awareness of the passage of time that is inherent in distant deadlines for significant events.

This morning during my 10 minutes of mindfulness, something interesting bubbled up. I randomly remembered myself on an airplane travelling back to Moscow to visit family about 2 years ago. I felt a strong urge to be that person again, a bit like when I’m on vacation and towards the end, with a sigh, I think back to how liberating the first day off felt. Or when I reach the last bite of some dopamine-explosive dessert, I think back to how happy I felt when it was just put in front of me. We all love vacation and desert. However, my wish to be 2 years younger makes little sense. I was in the throes of a challenging 70-80 hours per week medical rota. It took much ingenuity to carve out enough time to travel. Is it regret? It wouldn’t be fair to say that the last 2 years were somehow a waste of time in any regard. Why do I feel so drawn to the thought of going back in time?

Fear of opportunity cost

Aged 27, I frequently contemplate what it would go back to a previous point in time. I think it’s the understanding of the limited nature of time. I also worry about opportunity cost. In economics, there is the term opportunity (alternative) cost is the value of the option that we don’t choose when making a decision. [If I have 1 euro and buy a 1 euro can of Coke, I would have to forego the 1 euro Mars bar in order to have it. I would thus potentially worry about what it would have been like if they got a Mars bar instead.] The feeling is different to decision-anxiety. It’s not even about second guessing one’s choice, but more about imagining alternative paths.

The word decision literally means the cutting off – of other options. Thinking of the alternatives always reminds us of the unyielding nature of choice and how we really can’t literally “have it all”.

Robert Frost’s famous (infamous?) “The Road Not Taken” is a brilliant and often misinterpreted examination of the nature of choice. It is important to recognise the speaker’s deliberation: he says the roads are much the same: “just as fair”, “really about the same”, “equally lay”.

“The Road Not Taken”, a frequent feature of post-card philosophy, is often oversimplified to say that the speaker chose the less travelled road – and, woohoo, that’s amazing. It’s more complex than that.

The speaker admits that he left the first road “for another day”. While he knew he would never go back, the torment of admitting the final nature of choice is just too much.

One can get very detailed when describing their particular fear. I certainly don’t support the idea of including “fear of opportunity cost”, “fear of the passage of time” or even “fear of choice” as phobias into the DSM. Indeed, this is perfect ground for thinking by induction. Is there a common thread here?

Boiling down fears to a common denominator: could it be death?

Why does chronophobia affect students? Time forces them to deal with events that will affect serious aspects of their lives such as their future careers – and thus even more permanent things like social class, the kind of people they will be likely to marry and so on. Exam results’ effects are by no means definitive, but probabilistically they are significant.

It has become popular to say that there are only 2 human emotions: fear and love.

Everything negative is a form of fear. It kind of makes sense: anger is a way of defending one’s point of view, property or whatever other boundary. Being sad is a fear that one will never be as happy as they were before as a result of an event (not talking about depression here). Disgust is a fear that something will negatively impact one’s existence. You get the gist.

The other popular thought is that all fear is a form of the ultimate fear – of death.

Going back to chronophobia again, why does it affect the elderly? Time threatens the existence of the elderly. It threatens all of our’s existence, but the elderly are more aware of it – mostly for social and cultural reasons. Now, none of us are deluded enough to actually think we’re not going to die. However, as Ernest Becker points out:

we have 2 ideas of the self: the physical and the symbolic.

In my opinion, our rationality only extends as far as the physical self. We are preoccupied with ways to immortalise our symbolic self. As per the “Mahabharata”:

“The most wondrous thing in the world is that although every day innumerable creatures go to the abode of death, still man thinks that he is immortal”.

The recent debate that followed my discussion of the role of validation in our self-esteem sparked some follow on thoughts. In short, it showed that people with narcissistic tendencies experience much emptiness or even self-hatred – and validation is used to take the edge off. However, as all creatures who make choices, people with narcissistic tendencies are subject to avoiding pain and seeking pleasure (thank you, Dr. Freud). Clearly, they find narcissism more tolerable that the alternative. How could this be?

What if those who crave validation to feel good about themselves chose to be this way because the alternative – knowing that one is inherently valuable, without any validation – makes the thought of inevitable death absolutely intolerable? If one feels that they’re not that valuable, dying isn’t quite as scary or tragic.

Realising that a person is valuable, getting attached and then letting go is much harder than never getting attached – in this case to your self, as is the case with death. This devaluation allows people to cope with the fear of death. At the same time, the person with narcissistic tendencies maintains the upside of being able to work on “their immortality projects”, like winning medals and getting promotions. This is just a hypothesis of mine. I understand that I have no idea what Steve Jobs was really like. A lot of people say that he was an obnoxious narcissist. He said this, which happens to be congruent with my hypothesis:

Remembering that you are going to die is the best way I know to avoid the trap of thinking you have something to lose. You are already naked. There is no reason not to follow your heart.

There are other psychologically sneaky ways that we deal with the fear of death that have stood the test of time (well, since 1974 or so when “Denial of Death” was published):

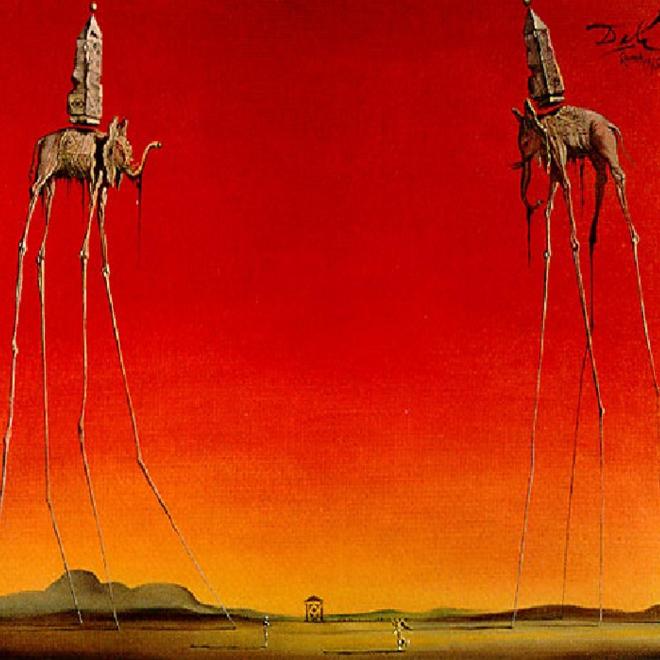

Becker argues that everything we do: writing books, starting businesses, having children are all ways to transcend – and not have to deal with – death.

It makes sense too: the thought that everything one ever does will disappear into oblivion is so hard to accept that in order to keep going we find ways to defy death’s erasure of our existence by leaving a legacy.

One’s own death is hard to imagine. It is as if we believe we will still be alive on some level after we die, but unable to act on our dreams and stuck reminiscing of the time we were alive and lamenting we didn’t do more.

If leaving a legacy isn’t an option, then one can choose to believe in the afterlife to help themselves cope with the concept death.

Paradoxically, dying may be a way to transcend death. Physical death could be a route to symbolic immortality. Just think of war heroes.

While death could explain a lot of our autopilot behaviour, we don’t seem to want to think about it very often. We are told to think positive thoughts instead.

To think, or not to think – about death

Constant reminders of death were common all throughout the last millennium: having a skull on one’s desk was kind of like having sticky notes or an extra mouse. An experiment where people were asked to write about death before they were asked about their country’s war efforts showed that thinking of death made people more enthusiastic about war -as it adds meaning, purpose, a sense of belonging, a feeling of impact…

The Stoics came up with a variety of reasons and hacks to not fear death such as the symmetry argument: fearing death is like fearing the fact that one wasn’t alive before one was born. I won’t go down the rabbit hole of explaining how to fear death less.

The purpose of my reflection isn’t to say we shouldn’t fear death, and it will all be fine. It is more of an inquiry into what behaviours of ours are motivated by the fundamental, underlying fear, which so far appears to be that of death. However,…

It’s not death we fear, it is not having an impact

Is it really death we fear? I think a better way of putting it is that we fear that we’re inconsequential, insignificant, that we made no difference through our existence.

For those who insist that it is a fear of death: it’s that of the symbolic self. For those who insist that our biggest fear is to not be loved: to have someone love one is probably the biggest impact one can have on another human being. Perhaps, it is the ultimate, or the one that really count. I am not sure. However, my point remains: it is about impact.

It could just be a millennial’s take on it. With a lesser role of traditional religion in today’s society, millennials have the unfulfilled need for meaning – and have a habit of finding it in the most peculiar places.

My recent discussion of meaning according to Nietzsche prompted many to comment that the fact that we die and that the universe will ultimately end (something to do with the Sun and physics) implies that there could be no meaning in our lives. I don’t follow this argument. To me, it is like saying there’s no point in eating because you’ll get hungry again. Clearly though,

for a lot of people death is the ultimate enemy in a game rigged against them.

I used the word impact above for a reason. I could have said consequence or meaning, but something stopped me. Both of those words are overused and call to mind all kinds of associations. Furthermore, I thought of animals. They are driven largely by the same evolutionary forces as we are, and I think we overestimate the extent to which animals are different. They may not have insight, but they are a reflection at least of how nature intended things. To illustrate, I will use an example I recall from watching a BBC documentary on giraffes. Two massive male giraffes were fighting for a female. How on earth do giraffes fight, I hear you ask. Well, they violently swing their entire necks to strike. The force of the swing is enough to shatter their skulls. The battle went on to the point of near death… for the sake of a female. The giraffes decided/were driven by nature to go that far just to reproduce – so death is less important than an opportunity to have impact, which, for giraffes I think is reasonable to assume, is to have progeny.

I don’t think that the fear of not having an impact is the same as the fear of failure. One can fail, but still achieve a lot and have an impact. Failure is defined in terms of a percentage of the way to realising a dream. Impact, or lack thereof, is much more real.

I feel that a human being on their death bed is likely to think of what impact they have had, not where they ranked compared to their dream.

On the bright side…

There is a “cure” for fear of choice

Going back to my own ENTP-torment of being more interested in talking about choices rather than actually making them, I am looking for some kind of resolution. N. N. Taleb, a favourite writer of mine, is popularising the concept of optionality. He argues that having options is a great thing:

Optionality is the property of asymmetric upside (preferably unlimited) with correspondingly limited downside (preferably tiny).

It’s not really a way to get out of making choices. Instead, it is a way to do what you were going to do anyway, but leaving cheap enough nets here and there to see if one day something nice washes up in one of them such that covers the cost of having had the nets n times over.

He argues against specialisation (i.e. going down too far in the decision tree of choices or going down to the end of just one branch). We are all familiar with specialisation success stories. The Nobel Prize goes to the person who studied a particular enzyme for 30 years. The startup that solves a specific problem in one particular niche is the one that does well. Kim Kardashian has one thing going for her, and she’s taken over the world…

Taleb reminds us that there are cemeteries of specialised ventures and people. Just because the successes that make into the media are specialised, doesn’t mean all of them are. Specialisation comes from the propensity to make choices. It is not the only way to achieve something. Hence, it is possible that the act of making choices is overvalued.

Richard Branson has over 400 companies. Is it because he is greedy – or perhaps because he understands that specialisation is a dangerous game to play? Venture capitalists and angel investors back things in a non-specialised way. All financial investors do. It may look like it is specialised on the surface, but it really isn’t. Biotech, or robotics, isn’t a specialisation. These are incredibly broad fields. It’s like saying blogging is a specialisation. Investors take directional bets once is a while, i.e. ones that really require a choice, but they do so in a way that for every 1 euro they invest, they stand to gain 10, and only invest a tiny fraction of their euros into these schemes. This is exactly congruent with Taleb’s definition of optionality.

I have fabulously rationalised away the pressure to make choices here. However, the real work is in putting oneself into situations where optionality can be exercised.

The older I get, the more I realise that there’s quite a lot of engineering involved in all of this. It’s not so much about going after specific visions, but creating situations where visions can flourish – and ultimately have an impact.

You may also like:

Millennial corporate office workers and their transgender bathrooms

As you know, I have a

As you know, I have a