This is concept art for a little book I am releasing soon. I am pretty afraid of her already (and I should be).

Credit: Milica Milić

This is concept art for a little book I am releasing soon. I am pretty afraid of her already (and I should be).

Credit: Milica Milić

Taleb established that the silver rule is more ethical than the golden rule, i.e.

“do not do unto others as you would not have them do unto you” rather than

“do unto others as you would have them do unto you”.

I think it is rather obvious that avoiding injustice is more robust than trying to pursue justice because not even the most well-intentioned and intelligent know what harm they could do as an n-th order consequence of their pursuits.

In opinion, it’s for the same reason why doctors try to do no harm rather than to make people healthy.

Taleb has been on Twitter a lot, and by god, he didn’t just take the red pill, he took the whole box. He used the terms “social justice warrior”, “white knight”, etc to talk about people who signal their generosity of spirit without being exposed to the consequences of that which they advocate. Next, he will be on Alex Jones.

He implied that the very prominence of Bernie Sanders is a testament to how unequal the Unites States became under the preceding presidency. He also brought up some jaw-dropping statistics about the dynamics of (in)equality: a large portion of the US population will be among the richest at some point in their lives, unlike in Europe where, if you are rich, you’ve been rich since the middle ages.

Taleb exposed a very interesting feature of atheism while calling it a “monotheistic religion”. I think what he was getting at is that pagan religions are inherently pluralist. There is a kind of competition between the gods, whereas monotheistic religions involve an absolute as, one could argue, does atheism (but not agnosticism).

Taleb spoke about not being comfortable to get naturalised in France, as he was entitled, as he wasn’t part of the culture (but would have been on with a Greek or Cypriot passport). He admitted to wanting to accept the honorary degree from a Lebanese university as an exception.

He backed the United States’ policy of making its citizens pay tax on all their income obtained elsewhere, to the United States. He endorsed a certain amount of protectionism.

This is a stark change from his stance in the now 11 year old The Black Swan.

He spoke once again about the benefits of decentralisation, the damage caused by regulation, etc. He mentioned the paradox of tolerating intolerance under a democratic system, but, in my view, didn’t address it properly.

He compared entrepreneurs to wolves and employees to dogs and argued that freedom always involves risk.

In a strange, conflicted way, he portrayed autocrats as entrepreneurs: it is easier to deal with a business owner (autocrat) than an employee (elected representative held accountable by committees and the media) when trying to make a deal.

Taleb argues that when it comes to language, the one that suits the most intransigent group and doesn’t inconvenience the majority becomes the lingua franca. Another example of this process is that a lot of schools don’t allow peanuts, or why commonly available juice is being labeled as kosher. He calls this the minority rule.

His argument about genetics is the opposite, the majority rule, as in the genetics of certain populations remain the same despite invasions.

I am not so sure he is right because what you find studying non-autosomal genetics (Y chromosomes and mitochondria) is that a version of the minority rule applies. It’s the same mechanism as why surnames die out and in theory, as time goes to infinity, we will all end up with the same surname.

Taleb denounces as charlatans the people who give advice without being held accountable for it. He feels that a life coach can only teach you to be a life coach and a professor can only teach you to be a professor. Does it follow that Taleb can only impart the knowledge on how to be a contrarian writer?

What skin does he have in the game? Reputation? Family? So do politicians, who he argues aren’t exposed to the consequences of their actions. He has long left his area of risk management and moved on to cultural, political and economic issues. I guess he is a successful practitioner of risk, a man who lived an interesting life and an erudite. He doesn’t impose his policies and regulations onto people. He does seem to have soul in the game as there appears to be consistency and integrity in his writing. It seems that he is doing it for posterity. Through his f*** you money, as he calls it, I think he has to an extent isolated his skin from the game. He seems to think this is freedom.

If you are going to read just one book by Taleb, I recommend Fooled by Randomness. Otherwise, yes. You can get it on Amazon.

Somewhere between trashy and literary, there is a set of historical detective novels about Erast Fandorin. I was a fan when I was younger and recently, the concluding book was released, Not saying goodbye. The character has a beautiful sense of duty mixed in with a XIX century James Bond style immortality.

Spoiler alert. Until he doesn’t. The ending was disappointingly cynical. Once again, he prioritised his sense of duty over his family, just like he did in the first book, Azazel, which I never really liked. The cynicism comes from the setting: orphans, an explosion… It’s almost like fate herself came around to avenge the death of his first wife for which he is arguably responsible. I felt he wasn’t. The author seems to think he was – after all this time.

I think the author’s main concern throughout his writing has been this sense of duty to the world at large – which he felt was impossible to combine with the duty to one’s loved ones. Alas, I think the author turned into a different man to the one who wrote the books that I really liked, namely The Death of Achilles, The Coronation and Special Assignments.

Ten. Billion. Dollars. A year.

That’s how much the self-help industry makes. That is actually more than make up.

A lover of books, I stopped looking at the best-sellers sections of book shops because they inevitably contain self-help books, about how to optimise this and maximise that. I spoke about books I regretted reading and definitely anything like self-help is in that category.

A reflection of our time for sure, with their “aspirational narcissism” and “predatory optimism”:

Where success can be measured with increasing accuracy, so, too, can failure. On the other side of self-improvement, Cederström and Spicer have discovered, is a sense not simply of inadequacy but of fraudulence. In December, with the end of their project approaching, Spicer reflects that he has spent the year focussing on himself to the exclusion of everything, and everyone, else in his life. His wife is due to give birth to their second child in a few days; their relationship is not at its best. And yet, he writes, “I could not think of another year I spent more of my time doing things that were not me at all.” He doesn’t feel like a better version of himself. He doesn’t even feel like himself. He has been like a man possessed: “If it wasn’t me, who was it then?”

The New Yorker article itself is a bit self-helpy, ironically, but has a few gems and a review of the literature, if it may be called that.

I think that for many people, improving yourself is happiness: seeing progress, seeing results of your work and what you have become as a consequence. So in theory we shouldn’t deride self help.

I don’t know what bothers me the most about it: the feeling of constantly being sold to? The relentless inward focus when a lot of these problems are better solved with the help of those closest to you? The idea of a cheap shortcut to “radical change”? All of the above and many more. In my view, self-help is definitely not the best way to improve yourself.

I also think that the generation below us aren’t going to go for it anymore. They prefer “not giving a fk” to getting rich and thin or dying trying. Of course, this won’t reduce the amount of money spent on the genre as it is highly adaptive in telling people what they want to hear.

Here is a “bored Elon Musk” type idea. (I get them a lot.)

Turns out, Kindle beat me to the punch:

“Unlimited Reading. Unlimited Listening. Any Device. Enjoy this book and over 1 million titles, thousands of audiobooks, and recent magazines on any device for just £7.99 a month.”

*It would go something like this:

Could still do it for non-Amazon platforms. Writers, whatcha think?

…

P.S. Awesome video by Jordan Peterson on existentialism.

Do you think that certain books should be kept away from children?

I would generally have said no:

Freedom of speech! No to censorship!

Being in touch with reality is important!

It’s preparation for the real world!

But then I realised that as a teenager I’ve read a few of those books and sometimes I wish I hadn’t…

When you think about it, Anna Karenina even is quite PG. Then again so is nearly all of Shakespeare. I think that it’s easier not to suspend disbelief with things written in super archaic or unfamiliar language – same with the Greek myths, hence they don’t hit as hard. Perhaps that’s the reason most of my books non grata come from the last 150 years.

Have you ever regretted reading a work of fiction?

I have a problem: I really don’t like giving up books I started.

Is the solution to read them to the end?

No, because they are either full of mistakes and fakes or mostly because they are shallow.

Is the solution to not read them?

No, because then I’d start living in an echo chamber and that’s bad.

Is there a solution?

Yes: entertain a point of view and be able to throw it in the bin without succumbing to the slavish “it’s in a book, therefore it’s right”.

Does that mean I should read everything?

Absolutely not. For me, the purpose of reading is to come across ideas that I am not familiar with.

I recently asked the Slate Star Codex reddit thread how they choose their books because modern non-fiction has been getting on my nerves. Some good points came up and I will add some of my own (relating to both fiction and non-fiction):

1. The main criterion to optimise for is the product of age and readability

For example,

Saw The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck on the best sellers book shelf?

Read Moral letters to Lucilius (1st century AD) instead.

Is everyone reading Fifty Shades of Grey? Anna Karenina (1877) is what you need.

Looking at Sapiens: a Brief History of Humankind?

Pick up The Lessons of History by Will and Ariel Durant.

Old books are free from copyright too, so you will easily find them online.

Readability is tough one. I have suffered through many a Shakespearean play. It’s not him, it’s me. I just find him difficult to understand. It happens to be worth it.

In general, the only disadvantage to old books is that they aren’t always intelligible on a practical level.

2. If the book is recommended by a friend, consider it and if you are stuck, ask a friend for a recommendation

Make sure they themselves have read it.

This is how I got into reading Nassim Taleb.

3. If it is on your favourite subject/sub-genre, older than 50 years and still relevant, it’s worth a read

Like Sherlock Holmes? You will probably like Hercule Poirot

4. If the author is a journalist first and foremost, don’t bother with it

Let’s not get political and mention names, but they usually have a lot of interests to defend

5. Authors who spend a lot of time in your part of the world are generally easier to read

Occasionally, for me, reading modern American authors feels like watching an informercial. I mean I really don’t want the first 3 chapters explaining why I should read the book, it’s already in my hands ffs.

6. Sample three random pages in the book: if a paragraph doesn’t make sense, the whole book it unlikely to make sense

This is what I do in book stores. Style is part of substance. When it comes to reading books by academics, this is especially important.

7. If the book itself promises to change your life, destroy as many copies as you can, so that our grandchildren are saved from the intellectual pollution

I could go on a rant, but I won’t.

There are obviously exceptions to the above.

In addition,

8. Books by the same author seem like a good idea, but this isn’t a reliable rule

J. R. R. Tolkien, for example.

9. Reviews aren’t very important

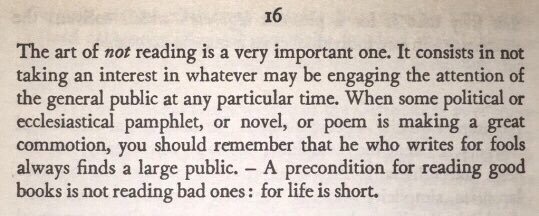

Arthur explains it well above.

Case in point: The Da Vinci Code is 4.5/5 on Amazon.

…

And what if you are too cool for books?

Who do you like to read online?

Maria’s Brain Pickings is excellent

The Brain blog is overly academic in its tone, but still nice

Massimo’s Footnotes to Plato is lots of cool philosophy

Lots of other blogs where I know, or feel like I know, the author.

The Russians have a law against offending the feelings of religious followers.

It came up again today because a magazine did a (somewhat) explicit photoshoot in a church they considered abandoned:

It turns out the church wasn’t entirely abandoned and was occasionally used. This may result in a court case against the model/photographer/publication involved: not because they perpetrated land belonging to the church, but because they offended people’s religious beliefs.

A man recently received a suspended sentence for catching Pokemon in another church for this reason.

Is the fact that the Russians want to protect the religious any different to the snowflakery millennials are getting accused of?

In West it is kind of the opposite, but the same principle applies. We’re most worried about offending those who fight for more modern things, e.g. non-traditional genders.

It’s a past time of mine to observe the parallels between two places that most people consider as different as night and day. And it allows me to ask: why is there such a global cross-cultural tendency to protect the feelings of minorities through law?

In a recent case, a woman was found guilty of involuntary manslaughter because of what she said. Of course, her words were evil. It was emotional abuse taken to the limit.

But can words really be equated to violence?

I think that this would only encourage physical violence by closing a steam valve. It makes little of victims of real violence. There’s something wrong with putting genuinely violent people in the same category with someone who likes to rant.

Incitement to hatred? Obviously it would be ideal if we all agreed and lived in peace and love. But assuming that we’re not moving to a utopia any time soon, isn’t it better to allow people to peacefully rant and speak freely than to encourage them to band into groups and get violent against the establishment which is what we achieve by marginalising them? In fact, ranters of a denomination could verbally spar with other types of ranters. Might it even be a healthy debate?

Perhaps non-violent hating is like a small forest fire:

“Small forest fires periodically cleanse the system of the most flammable material, so this does not have the opportunity to accumulate. Systematically preventing forest fires from taking place ‘to be safe’ makes the big one much worse.” – Nassim Taleb. Antifragile : things that gain from disorder.

Similarly, marginalising the “haters” just leads to real violence.

Having said that, I can relate. I have often felt like I needed trigger warnings. I get very upset at certain images in films and documentaries. But I would never feel that someone owes it to me to prevent me from them: if I made a choice to watch a film, that’s just part of the consequences. Being honest, I don’t watch that many films for this precise reason.

Virtually every book or film I process results in an overwhelming spillage of thoughts and emotions (hence, this blog). In fact, I am still haunted by a number of books I read.

When I was in school, we were always given a book list for the summer. Part of me wishes I’d never read Three Comrades and The Collector. Part of me is enraged that there wasn’t a trigger warning on those books. But by reading these books I learnt what I do and don’t like – and why.

But let’s just imagine that words aren’t violence and flip the question: should it be a crime to offend people’s feelings?

P. S. I am meant to be working on Philip Larkin‘s poetry, but I’m not a fan, hence, all this 🙂