In the professional medical world, Medscape is probably the most trusted up to date online resource. I am delighted to see that yesterday they published an article that highlights some of the more challenging and distressing aspects of meditation based on a recent scientific paper in PLOS One.

The reason I am so glad is that it means we’re moving to a different approach to meditation, one with more well-warranted rigour in how people talk about this intervention and away from the perception that this is something without side-effects.

Crux of the study:

- the challenging aspects of Buddhist-derived meditation practices are well described in Buddhist tradition but are less so in Western scientific literature

- the researchers interviewed nearly 100 meditators and meditation teachers from each of three main traditions: Theravāda, Zen, and Tibetan.

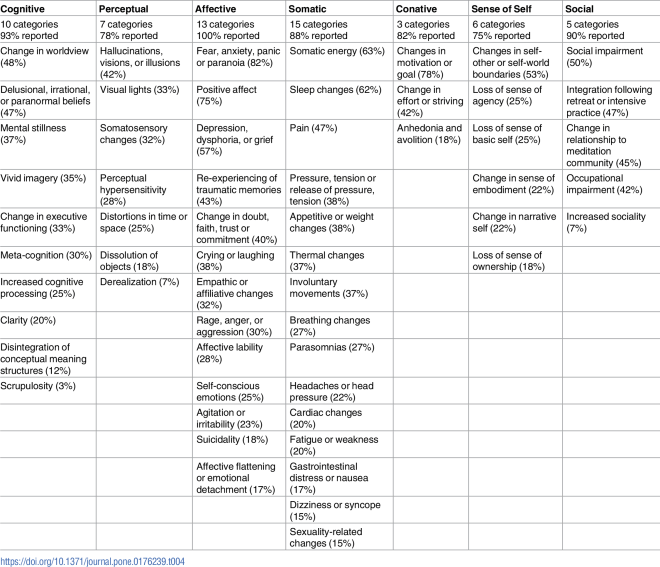

- the researchers developed a taxonomy of 59 experiences organised into seven domains: cognitive, perceptual, affective (emotions and moods), somatic (relating to the body), conative (motivation or will), sense of self, and social.

- all meditators reported multiple unexpected experiences across the seven domains of experience.

- the duration of the effects people described in their interviews varied widely, ranging from a few days to months to more than a decade, the investigators report.

- some meditators reported their feelings, even the desirable ones, went too far or lasted too long, or they felt violated, exposed, or disoriented.

- meditation experiences that felt positive during retreats sometimes persisted and interfered with their ability to function or work when they left the retreat and returned to normal life.

- the meditator’s practice intensity, psychiatric history, trauma history and the quality of supervision are important factors that influence the meditators experience, but not for everyone.

- the study highlights that the one size fits all approach isn’t ideal: “The good news is that there are many different programs out there and different practices available, and with a little bit of homework and informed shopping, someone could find a really good match for what they are after,” she said. “But I think often people just sign up for whatever is the most convenient or the best marketed, and it’s not always a good match for their constitution or their goals.”

Dissecting the side effects

Here are the reported side effects with the percentage of people who reported them in brackets:

It’s fascinating to note that nearly 50% noted a change in worldview. Open mind, new philosophy – fair enough. I would be on the fence about saying that I have a different world view because of meditation. It’s clearer, it’s calmer, it’s more adaptable, but it’s not really changed. Thus, it is possible that people who try to meditate are often looking for a new worldview or are quite suggestible.

Nearly the same number of people reported delusional, irrational and paranormal beliefs! I guess this is all based on Buddhism and there is a strong religious element to it. However, people were clearly made uncomfortable by it. I certainly experienced this: this is why I tread carefully when I go exploring meditation resources. A huge number of them are zealous, either for reasons of unquestioning devotion, or commercial ones. Snake oil requires faith.

Again, over 40% reported hallucinations. Just as a reminder – delusions and hallucinations are the key ingredients of psychosis and good reason to admit someone to a psychiatric ward. Obviously, these must not be quite as persistent as those associated with psychiatric disease, but if I had seen this table before starting mindfulness, I would have thought much more carefully. In this sample, 32% of people had a prior psychiatric history. This doesn’t explain how common all these DSM-sounding symptoms are among them.

Fear, anxiety, panic or paranoia came up for over 80% of people. I think is more a reflection on the sample than on meditation. Why to people meditate? Often they come upon it as a cure for anxiety. Indeed, in my experience, besides actually getting rid of the anxiogenic stimulus, meditation is a great method to deal with it. Depression was very common too at over 50%. Anhedonia and avolition – being unable to experience pleasure and not having any desire to do anything – are hallmarks of depression and were experienced by 18%. Personally, anxiety has always accompanied meditation in some way or another, but not in a bad way. It’s a little bit like saying that exercise cause shortness of breath. However, panic and paranoia are step to far.

Where there are mood changes, there are autonomic function changes and indeed they seem to have been affected too: level of energy, quality of sleep, appetite, etc. It’s unfortunate to note that many of those changes were negative with common reports of fatigue and pain.

As expected, 75% of meditators had their mind bent by Buddhist approaches to the self. We also know from MRI studies, that the anatomical self, seated in default mode network is modified by meditation, so this is expected.

Clarity, meta-cognition and increased cognitive processing – that’s our thinking clearly box ticked.

What does all of this mean?

To meditate or not? Meditate, but proceed with caution, a healthy balance of open-mindedness and scepticism – and preferably with supervision. In the words of Dr Walsh, it’s important to be challenged, but not overwhelmed.

As for me, I often take breaks from meditation. If it’s not happening, I don’t force myself too much. Thirty seconds of mindfulness is better than ten minutes of desperate striving effort and then feeling exposed, lonely and inadequate. To give it a Buddhist twist, we can think of the experience as if it is the weather. You may have decided that you are jogging today, but if it is stormy outside, it’s better to be a bit more adaptable, stay at home and practice your planks. Same here.

Reference:

Lindahl JR, Fisher NE, Cooper DJ, Rosen RK, Britton WB (2017) The varieties of contemplative experience: A mixed-methods study of meditation-related challenges in Western Buddhists. PLoS ONE 12(5): e0176239. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176239

P.S. Have a look at this Christian blogger explaining the emotional conflict she experienced when exploring yoga. It’s not important to be religious to understand that imposing one system of beliefs over another, whatever it may be, can be highly distressing.