This is one of those articles that I wrote for myself: for those mornings when the only things you want to do are browse Facebook and watch BBC1, or at least you think you do. Then you remember that you’ve about 20 problems to solve that day and get that feeling in your stomach like both your adrenal glands just emptied their contents into your bloodstream.

1. Enter into deep work mode

Wall off some distraction free time. The phone goes on airplane mode. Close all the tabs you don’t need.

Let’s be honest, if you are reading this, you are probably dealing with quite challenging and cognitively demanding.

These things require extreme levels of focus and uninterrupted immersion for an effective resolution.

As such, the goal is to enter into a state of flow. It is a paradoxical mix of mindfulness and being very goal-directed at the same time. Flow, also known as the zone, is the mental state of operation in which a person performing an activity is fully immersed in a feeling of energised focus, full involvement, and enjoyment in the process of the activity.

2. Do a brain dump

If you are at a loss, the thoughts are messy and you don’t know where to start, an unstructured flow of consciousness style “brain dump” is required. It straightens out circular ruminations and allows the writer to identify what is really wrong. There is something liberating about getting things down on paper. You can always throw it out. Nobody has to see it. It is only for you to see.

In the best possible way, it lowers expectations and gives you the licence to be really honest.

I am putting my money where my mouth is with this tip: a lot of this blog is really me writing for me. I often reread what I have written because it answers questions that bother me (and catch a few typos on the way!) It turns out that the same questions bother a lot of people, hence our little community.

3. Draw a spider diagram

Difficulties in solving problems often arise from the fact that problems are interdependent, they are not isolated. Drawing a spider diagram (a mind map) is a very good way to figure out what’s going on.

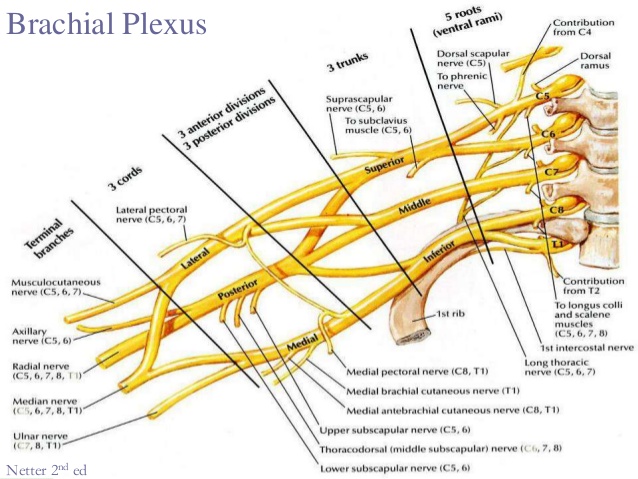

As a one-time medical student in the rather fundamentalist anatomy department, I had to learn everything about the brachial plexus (pictured above). The structure was just the starting point of what I needed to know. The the origins at the spine and the muscle activation were at least as complex on top of that. I drew a spider diagram.

When my father was splitting from his second wife and I arrived home to find my stuff packed away in boxes by the latter, well, I also drew a spider diagram. Because I needed to understand what’s going, what everyone is thinking and where to move (not just literally) from there.

This approach to thinking is resonant with the structure of our brain with its nodes and links.

4. Make a to-solve list (not a to do list) and tell a story

Lists are great, says the ENTP. Even checklists. They really are great because they give us a sense of control. I have studied motivation in great detail as I deal with students doing their final school exams to get into college. They keep asking me about motivation. These 17 year olds have the most fine-tuned BS filter on the planet, so I really need to try hard. I finally found a solution for them, which is: a sense of control.

Feeling in control is the key to being motivated.

There is a mountain of evidence about this. However, a small study done on nursing home residents really illustrates it best. Some people who go into nursing homes don’t do well and fade away in less than 6 months. Others seem more alive than any of us. What’s the difference? Well, as one of the lively 85 year olds explained: “I trade my chocolate desert for a piece of fruit from one of the other guys at every dinner”. Why? Doesn’t he like chocolate? The answer lies in the fact that now he has control: in an environment where you are told when to sleep, where to sit and when to take your tablets, it is crucial to eke out a sense of control by being in charge of something small like that.

How do you structure a list? There are two great ways:

- list of problems to solve

- a chronological story-plan

A plain to-do list just makes you feel like you are doing chores. A list of problems to solve automatically gives both purpose and perspective.

As for the story plan, there is something about our brains that makes us dead set of prioritising stories over any other kind of information. It is therefore important to tap into that. A fair portion of NLP is snake oil, but their emphasis on story-telling is right on. Things seem far less daunting if you write them down on a piece of paper as bite-sized steps. For example, recently, I have been moving between countries. It’s an overwhelming amount of paper work, a complex process with many catch-22’s to machete through like you need a lease to set up utility bills, and a utility bill to set up a bank account and a bank account to set up a lease. By writing it down, it is easier to see solutions and the impossible soon becomes possible. There are 2 reasons for this:

- we find it difficult to store long sequences in our heads, so a written down prop is key (this is mentioned a lot in Thinking Fast and Slow and GTD)

- by going through the steps required to build out the story, we think of the entire contexts – the things we would have otherwise forgotten about

5. Snap out of being on rails by getting perspective

It’s precisely when we are “on rails”, when we have some kind of contagious emotion unfolding in us, when we want to “just get this done”, that we need to pause and switch to something else. Ideally, we would go straight to taking 10 minutes to be mindful, but for most of us mortals that just seems impossible. Instead, it is a good idea to think of something completely different.

Let’s say there is an enraging email that you can’t wait to respond to so as to make it go away. Mindfulness? Now? No!…

To ease yourself out of the hijacked state, think of something completely different, preferably something even more challenging, that makes the original issue seem like nonsense.

Recently, I was dealing with an unruly real estate agent who just wouldn’t listen and kept sending me emails with unreasonable demands. I thought to myself: there are lots of people who don’t have this problem – because they simply cannot afford to live on their own. It’s not even that it made me feel grateful and empowered, that’s not the point, but it gave me perspective and an ability to deal with the tyrant in a way that accomplished my aims rather than just telling them “for the n-time, will you…”

6. Take 10 minutes to meditate

It is when we are busiest that we need to take the time to be mindful.

I recall Ray Dalio talking about it. Yes, the guy is filthy rich, but I can just imagine him losing a billion bucks (it happens in that business) and going into his office to do his TM routine. What else would he do? Shout at the researchers for not seeing into the future? The traders for not getting out of the trade earlier? There is no point. It is much better to get centred again and then do what is actually going to help the situation.

7. Have a cup of matcha, or any good green tea

I’ve always loved green tea. However, after my trip to Japan, it became clear to me that there is something quite magical about certain varieties of green tea. I am a big fan of Ippodo and specifically Ummon-no-mukashi.

Like salbutamol opens the bronchioles, this stuff clears the head.

For those who aren’t keen on concentrated green goo, a cup of Hosen Sencha will do wonders too. The way the Japanese drink tea is more or less an exercise in mindfulness, so I would make use of that aspect too. It is part of my morning routine. It is especially something that people who can’t drink coffee should consider. Unlike coffee, matcha doesn’t give you a jolt of energy and then a come down, but a steady state of clarity.

8. Listen to some upbeat classical music you’re not very familiar with

Listening to something you know well calls in all kinds of associations and other hardcoded Pavlovian nonsense we don’t always need.

Thankfully, there is so much classical music out there, we’re unlikely to ever be stuck. Some may prefer house music. Sometimes house music has lyrics or distracting sexy sounds. My personal recommendation would be listening to Béla Bartók or anything played by Lang Lang, a virtuoso pianist. You may also like some great apps for mindful focus.

9. Jump in for a very short burst of exercise

Even two minutes of HIIT or a quick few sets of sun salutations are likely to be quite refreshing. In an upcoming post, a neurologist will explain that

our adrenal medulla – the seat of the flight-or-fight response, the ultimate thinking and creativity saboteur, is controlled more by the motor cortex than it is by the conscious decision making centres.

10. Don’t even attempt it if you are tired

Sleep is massively undervalued in today’s society. Sleep deprivation has incredibly significant effects. Not that much sleep deprivation at all will give you the insulin resistance of a type 2 diabetic.

All the most intelligent people I know sleep at least 8 hours a night and don’t even attempt anything cognitively taxing unless they are refreshed.

This is obviously challenging for people with young children, for example, but if you can work to put yourself in a situation where you can be refreshed, it will really pay off.

11. Have a shower

Special troops are told to prioritise staying clean even in extreme circumstances. It raises morale. There is something life-affirming about water and cleanliness. The chemical changes, such as an oxytocin increase, is likely to have a positive effect on one’s emotional state.

12. Talk to a human being

We are social animals: that is just how we’ve evolved. Not all problems need to be attacked by the entire tribe, but calling in help is required sometimes because other will help us navigate through our weaknesses, see new perspective and just feel like a human being again.

Mindfulness helps me to stay in touch with reality. Walking is simply good for us human beings, as N.N. Taleb says. He can nearly match a word count of his essay writing to his miles walked. It’s near impossible to stay cognitively refreshed unless one reads. Exercise goes without saying.

Mindfulness helps me to stay in touch with reality. Walking is simply good for us human beings, as N.N. Taleb says. He can nearly match a word count of his essay writing to his miles walked. It’s near impossible to stay cognitively refreshed unless one reads. Exercise goes without saying.