Anthropologists have long known that when a tribe of people lose their feeling that their way of life is worthwhile they […] simply lie down and die beside streams full of fish.

Ernest Becker

What is nihilism?

Nihilism is a confusing term. It can mean rejection of societal norms (political nihilism). This is not what I am going to discuss here.

I will talk about Nietzsche’s definition of nihilism: the radical rejection of value, meaning* and desirability.

I think this communicates the most important concepts. Of course, there are more specific definitions, so I will get them out of the way here. There is moral nihilism that says that there is no right and wrong. Epistomological nihilism says there is no universal truth or meaning. Existential nihilism rejects meaning in life.

Stoicism vs nihilism

Stoicism is really en vogue these days. Seneca’s writings have grabbed my attention early last year and haven’t really let go. First, his Moral Letters are incredibly easy to read – compared to most undigested original philosophical texts (e.g. A. Schopenhauer). Second, they make one feel good, a bit like after watching Pulp Fiction. I was starting to wonder – what’s the catch? My “too good to be true” radar was going off.

Here’s a short summary of Seneca’s views:

- life is set in circumstances that we’ve no control over;

- it is possible to get through life by working on our response – not on the circumstances;

- there is no need to fear death because

- it is just like the blissful nothingness that came before we were born;

- it would, so to speak, “end the heartache and the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to”;

- we didn’t earn life – it was given to us by circumstance. Hence, we cannot expect to hang on to it.

This doesn’t sound so bad. In fact, it is quite resonant with the ultimate optimist Viktor Frankl: “When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves” and more or less the basis of modern day talking therapies like CBT and REBT. However, Seneca is quite pessimistic. Having re-read his letters a number of times, I picture him as a man who barely endured his life.

Any modern psychiatrist would say Seneca had a passive death wish.

It’s also interesting to remember that he was one of the wealthiest people of all time. Here’s a telling quotation from Letter 65:

“The wise man, the seeker after wisdom, is bound closely, indeed, to his body, but he is an absentee so far as his better self is concerned, and he concentrates his thoughts upon lofty things. Bound, so to speak, to his oath of allegiance, he regards the period of life as his term of service. He is so trained that he neither loves nor hates life; he endures a mortal lot, although he knows that an ampler lot is in store for him.”

Nietzsche famously pointed out that Christianity is nihilistic in the sense that it is denying the value of one’s current existence and instead placing it on a dream of a better afterlife.

By that same logic, Seneca too seems nihilistic. One might argue that in the context of Seneca thinking of death – it is kind of hopeful.

Nonetheless, Seneca belittles the value of the current life, encourages escapism and hope for, essentially, life in heaven after death.

At the same time, Seneca repeats that we have limited time on Earth and we better use it wisely. Just like Christianity, this philosophy appealed to all strata in society. Using either philosophy, anyone could be a hero by thinking themselves so. In a sense, one is less responsible for their actions as this world doesn’t really matter. Certainly, making the right choices matters – as it will be assessed for the purposes of a heaven vs hell decision, but it presents life as something that happens to a person – and the person has little agency. Having said that, much of what Seneca demands of Lucilius could safely be called overcoming-oneself, a cardinal virtue according to Nietzsche.

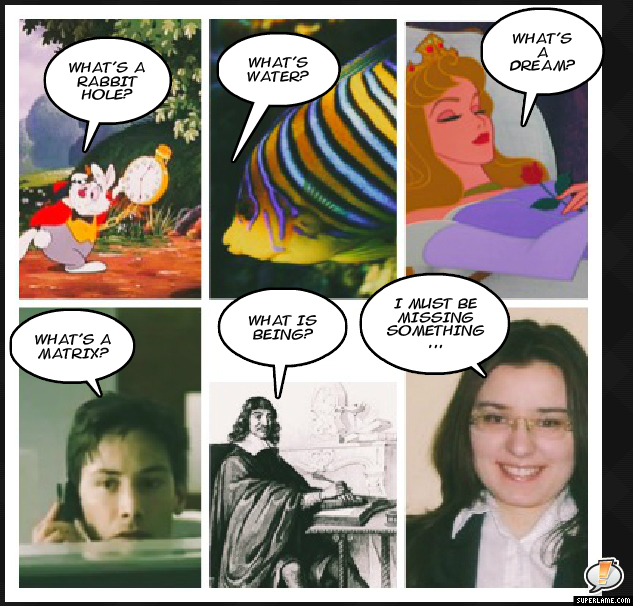

Meaning by school of thought

Unbound by any aspiration to philosophical scholarship, I have taken the liberty of making these one liners on how different schools/philosophers viewed meaning:

Stoics: there is meaning, it is to be wise and kind;

Schopenhauer: there is meaning; awareness of suffering and death create the need for meaning;

Buddhists: there is meaning, but it is ambiguous;

Hinduism: there is meaning; it is to shed the illusion and realise the unity of the universe;

Christianity: there is meaning; the meaning is to live so as to attain entry into a superior world;

Nietzsche: there is meaning; meaningful suffering is sought after, meaningless suffering is a curse – more on this later;

Nihilists: there is no meaning.

A nihilist’s escape routes

Being a bone fide nihilist is intolerable: there’s nothing to wish for, nothing makes a difference – like the tribes that encountered Western culture described by E. Becker in the epigraph, one may as well lie down and die. It’s a state fundamentally indistinguishable from severe and enduring depression.

Those who proclaim they are nihilistic and still go on about their lives as if nothing’s wrong are probably hedonistic, or have some kind of meaning they simply don’t call meaning. Or, they are like Anony Mole who appears to think that meaning is a psychological hack to staying motivated to live on, but ultimately hypothesising that there is no meaning at all.

For someone who doesn’t see meaning in life there’s another option, however. It is to defer meaning to one’s next life. In this sense, Christianity is a form of escapism away from nihilism.

In Christianity, the purpose of life is to live one’s current life in a certain way and attain entry into an alternate, “real and true” world – heaven. At first glance, it would seem that Nietzsche is overreacting by accusing Christianity of being nihilist. Christianity is full of ways that make this life meaningful. On closer reflection, the motivation behind acting according to the tenets of Christianity is that someone, from a place that we all really belong in, said that it is the right thing to do. This life is only a smoke and mirrors version of the blissful life in heaven. Nietzsche rejected true world theories as nonsense. He demonstrated that it was an assumption of his – and ultimately unknowable. Richard Dawkins says it’s intellectual cowardice to not come down on one side or the other. I think it is intellectual cowardice to not admit that there are certain things that we just don’t have a way of knowing.

Despite his rejection of true world theories, Nietzsche understood that they are the fabric that holds people’s lives together.

Of course, there are many more true world theories than Christianity, but it is the one that dominates the Wester world today. For example, Marxism is a true world theory – yearning for a future utopia. Nietzsche also argued that a Christian heaven helps the human sense of self: it is kind of validating to know that, really, one belongs in a special true world – not here.

Pema Chodron wrote about the psychology of our need for such a world in an accessible way. [There’s a funny story to go with that. I was sitting on the beach right after reading Chodron, reflecting on the ways in which we’re conditioned to want a fatherly God. An elderly man approached me and wondered if I was OK – I guess I must have looked distraught. It’s rather unusual for a man in his 80s to approach a random person on a beach, so I was wondering what’s going on. He didn’t say much, just asked again if I was ok and if I like reading. He reached to hand me a brochure – looking directly at me – and said only this one thing: “Oh, and there is a God”. I thanked him, mind-boggled. After he walked away, I looked at the brochure – turns out he was a Jehovah’s witness. I didn’t know they mind read.]

Besides turning to true world theories, there is another way to avert the pain of nihilism.

Like David Foster Wallace pointed out, there’s no such thing as atheism. We all believe something.

Science slowly becomes scientism and provides explanations for things it can and cannot explain. Following a political movement gives a sense of belonging. Our culture is a kaleidoscope of options for all tastes.

Searching for meaning is nihilistic

Nietzsche argued that asking the question “What is the meaning of life” and demanding an external answer by some superhuman authority diminished the value of the person asking – as if it comes from a lack one’s faith in their own ability to figure it out.

Nietzsche argued that nihilism arises when people get disillusioned with their default set of beliefs – let’s say beliefs that are inherent in one’s cultures – and take this disillusionment to more generally mean that no beliefs could ever be satisfactory.

This view of nihilism is once again almost indistinguishable from depression. Nietzsche expressed it best here:

“A new pride my ego taught me, and this I teach men: no longer to bury one’s head in the sand of heavenly things, but to bear it freely, an earthly head, which creates a meaning for the earth.”

Prof. Nietzsche’s meaning of life

So what did Nietzsche himself think the meaning of life was? It was to realise one’s inner potential.

Nietzsche believed in radical responsibility: it is only ourselves who we have to blame if we miss our life’s calling.

To him, we weren’t all born human. We become human by realising our potential. This is what he meant when he said “become who you are”. Fear and laziness are our ultimate enemies. Incidentally, this sounds like it is straight out of Seneca’s writings. Nietzsche claimed there was a higher self, a kind of will that dragged us to become who we are. To me this is terribly reminiscent of a true world theory albeit one confined to the self and to this life. His method was through setting difficult goals pursuing which elevates the soul. Congruent with the traditions of Buddhism, Nietzsche argued that suffering isn’t inherently bad – and one doesn’t need to immediately try and fix it or worse, distract oneself away from it. It is an opportunity for growth and wisdom, according to Nietzsche.

I guess it comes down to awareness, adaptability and agency again. This whole piece makes me sound like a Nietzsche fan girl. In a sense, it’s true, but he was a bit too anti-social, self-contradicting and melancholic for my liking. I will put that in more analytical terms at a later stage.

You may want to read

Kevin Simler’s reflections on meaning

Schopenhauer’s genius and mindful boredom

*[To be clear, we’re talking about meaning to a given person, not some universal, objective meta-meaning because ultimately an attempt at identifying this universal meaning will always be the meaning to the person thinking about it, or a projection thereof. This is one of the reasons humans are so naturally self-centred. David Foster Wallace describes it well here. As seen above, none of the major philosophies really even try to answer what the ultimate meaning of the universe is. This is probably because the question isn’t asked very often. This author is more interested in the tangible psychology of it – than the unknowable philosophy].

On the subject of the necessity of stupid work:

On the subject of the necessity of stupid work: